Hébert's men (train like them, look like them.)

"Countryside parkour" as the fastest path to a statuesque physique

This is part 10 of an ongoing series bringing Georges Hébert's "Natural Method" training protocols to an English-speaking audience for the first time.

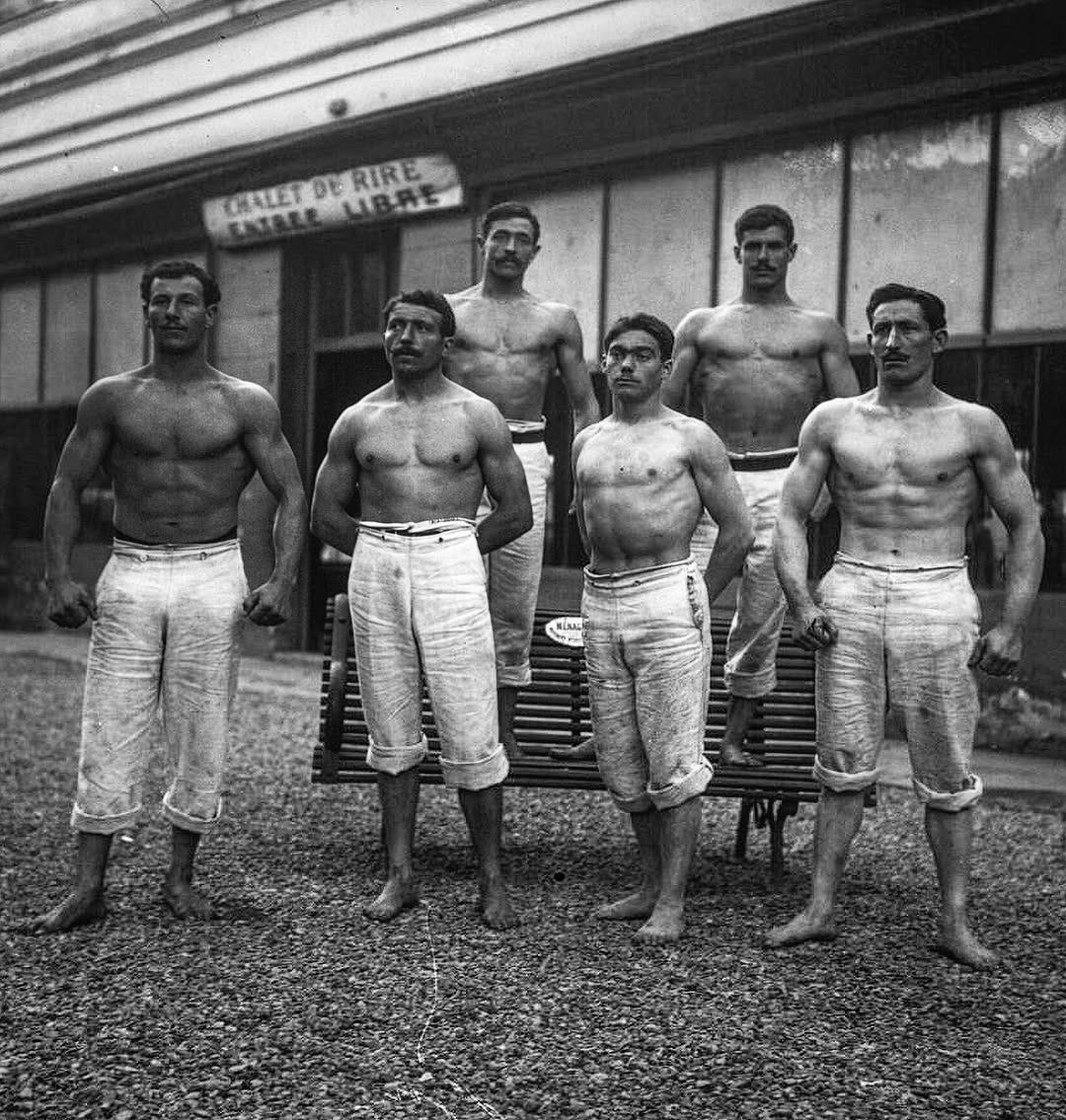

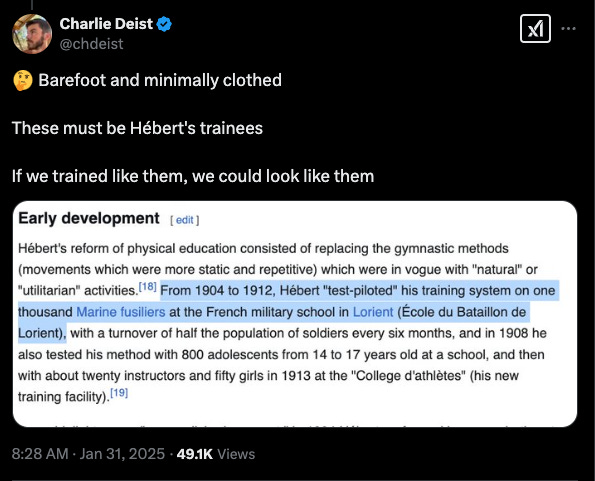

A few weeks ago, I was mindlessly scrolling X on the couch when I happened upon this vintage photograph of French “fusilier” marines from the 1909:

"Hey!" I thought, "I know that look!"

These were clearly Hébert guys. Barefoot, minimally clothed, and standing with unmistakable posture: upright, open-chested, and ready. Their statuesque physiques showed the trademark Hébertiste development—strong core muscles (transverse abdominus) creating an "inner corset" that conveys strength without bulk.

If we trained like them, I noted, we would look like them.

The reply racked up 50,000 views in days. Why? I suspect it’s because people recognize true vitality when they see it. More than that, they desire real role models (not just museum busts) who can help them obtain it.

While today's fitness influencers showcase swollen, hunched physiques built in climate-controlled gyms, Hébert’s men embodied something different—functional strength developed through practical movement in natural settings. It’s a much more virile strength. Sure, some of the guys in the photo are obviously flexing, but the one in the front row second from left, for example. looks like he is standing in his natural pose.

I'm not claiming to match these men's physiques, but during periods when I've consistently practiced Hébert's methods, I’ve found that my body transforms remarkably quickly to meaningful demands. These aren't unattainable physiques requiring endless gym hours. Hébert insisted on efficiency, with his ‘maintenance sessions’ averaging just 20-30 minutes.

What matters is that your workouts incorporate the right elements to trigger an epigenetic shift. Stationary calisthenics and conventional sports won't cut it. You must become an "athlete of life," engaging all your physical capabilities through natural, practical movement—often outdoors, sometimes barefoot, always minimally clothed.

Previous Installments

Chapter 1: Principles of Natural Movement

Principles of Natural Training (Sections 1-3)

The Proper Training Session (Sections 4-6)

The Lost Art of Relaxation (Sections 7-12)

Finding the Sweet Spot (Sections 13-17)

Rigor + Nature = Vigor (Sections 21-26)

Strength in Song (Sections 27-33)

Chapter 2: Conducting the Lesson

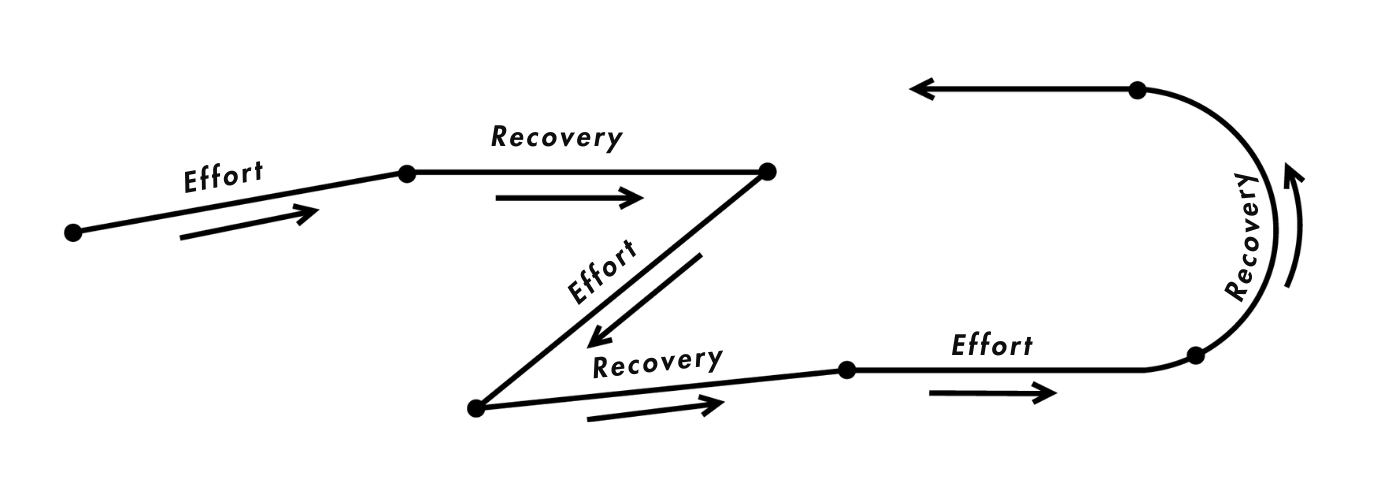

The Wave Pattern Principle (Section 1)

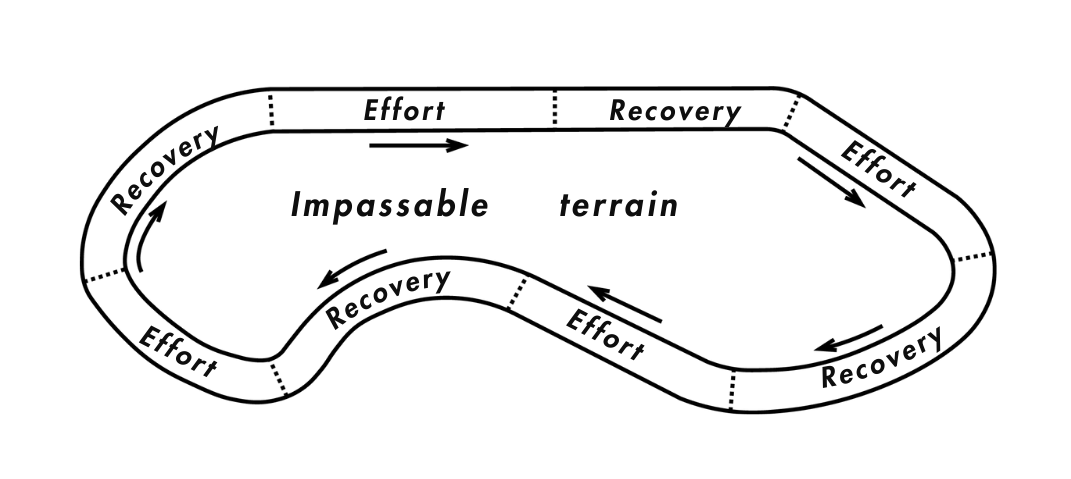

If you've been following this series, you know that Chapter 1 introduced the philosophy of the Natural Method, while the first part of Chapter 2 so far has covered the ingenious "wave pattern" for training groups on a field.

But what if you don't have a proper training field? Or what if you're ready to take your training beyond controlled environments?

That's what today's installment addresses. Hébert outlines how to adapt his method to any environment—from narrow garden paths to wild forests.

For those who find traditional fitness boring or can’t motivate themselves at the gym, Hébert's wilderness approach offers a refreshing alternative. Instead of trudging along on a treadmill or counting dumbbell reps, you're scaling rock faces, crossing streams, and navigating varied terrain.

Translation challenges abounded in this section. The French term "parcours en pleine nature" could almost be rendered as "countryside parkour," but I've chosen "wilderness session" to avoid confusion with modern urban parkour—which, while derived from Hébert's methods, now carries associations with acrobatics that are far removed from his approach. The French "bonds et contre-bonds" becomes "bounds and counter-bounds," periods of alternating effort. Sprinting and resting, like a lion hunting.

If you've ever felt that childlike excitement scrambling up a hillside or balancing across a fallen tree, you've experienced what Hébert built his entire system around.

Our bodies are built for this kind of movement.

About 15 years ago, I experienced a chronic illness that left me without much lust for life or desire to do my go-to exercises like going to the gym or city running. What I did find, however, was that I could motivate myself to lift a log (which happened to be placed conveniently on the side of a track where I used to jog). I discovered Erwan LeCorre’s The Workout the World Forgot, and it woke my body from its slumber into a kind of primal frenzy. The inner motivation translated into vigorous outer movement. I built stamina and was able to overcome my chronic fatigue by feeding my body with what it perceived as real-world challenges—the kind completely missing from our modern society.

The wilderness session is the pinnacle of Hébertismé:

No specialized equipment needed—just your body and the natural environment

Built-in variety that prevents plateaus and boredom

Practical skills developed rather than isolated muscles trained

And perhaps most importantly:

The connection with nature that re-aligns you with your nature.

If you have kids, the wilderness approach is especially fitting. I am living on a 20-acre rural property with woods, paths, creeks, and rocks. When I take my kids out, they naturally engage in many of Hébert's movement families—climbing trees and rocks, carrying branches, and balancing across logs. They might not hit all ten movement families in a given romp, but they intuitively gravitate toward the movements ones that develop core capabilities.

Compare this to American PE classes that focus primarily on team sports, leaving the less athletically inclined children marginalized and inactive.

I favor a two-pronged approach to bringing back these methods:

In cities, we can reclaim spaces like soccer fields and athletic stadiums for proper Natural Method training—ideally incorporating this approach into physical education during school hours.

In rural areas, we can establish “Hébert centers” as training grounds for instructors who can take this vision back to urban communities.

This second prong is part of my medium to long-term vision: creating the first American Hébertiste training center right here in beautiful Bangor, California—complete with a dedicated obstacle course and “plateau,” combined with the existing obstacle course provided by the terrain.

The Concise Guide fills in much of this vision with a concrete picture of what an ideal session looks like. I'm indebted to Georges Hébert's grandson Jacques, who entrusted me with the French manuscript of this work. While our European counterparts are moving towards an official organizational structure for Hébertistme, I believe that America represents the most fertile soil for a revival of these ideas in a grassroots, organic fashion.

For one, we are in a more advanced stage of the health crisis. The sudden rise of the Make American Healthy Again coalition signals that people are ready for radical solutions to the epidemic of diseases that RFK Jr. campaigned on.

Childhood obesity won’t be solved with jumping jacks.

If you’re looking to get started you don't need to overhaul your entire fitness routine overnight. Start with these three steps:

Find a natural area near you—a park, trail, or even a schoolyard with varied features

Identify natural obstacles for each movement family (something to climb, balance on, lift, carry)

Move through the space for 20-30 minutes, alternating between higher intensity "bounds" and recovery "counter-bounds"

Since resuming this translation project, I've been motivated to get back out in my own backyard and revive my obstacle course ambitions. The truth is, the obstacle course is already there—I don't need to install fancy equipment or construct elaborate structures. The trees, logs, slopes, and rocks provide everything needed. The hardest part is simply getting into the habit of going out and doing it. You don't need perfect conditions or a meticulously designed course. Just get out and move.

In the next installment, I’ll conclude the series with Chapter 3, on Hébert's instructions for designing a training session. Until then, I challenge you to step off the treadmill, leave your fitness tracker (even your phone) at home, and rediscover what your body was built to do.

Your primal self is waiting.

And now, without further adieu… here’s Hébert:

Chapter 2 - Conducting the Lesson

2. Most Common Mistakes to Avoid when Leading Groups on the Field

The principal errors that instructors must avoid when leading groups include:

Making multiple groups wait motionless at the starting base before launching them across the field (causing congestion at the start due to poor regulation of pacing)

Launching a wave across the field before the previous one has cleared, or has sufficient time to clear the finishing base (resulting in crowding and disorder at this base)

Returning along the lateral bases at high speed or in a state of muscular and nervous tension

Starting a wave before students have established proper lateral spacing from one another

Starting a wave without clear instructions regarding the starting position (prepared or not), the mode and pace of movement, the exercise to be performed, its execution mechanics, repetition count, or duration

Allowing students in a wave to cross paths, bunch together, zigzag, or jostle one another instead of requiring each to progress directly forward

Commanding impractical, conventional, or fanciful exercises that serve no useful purpose

Having students repeat useful exercises with inappropriate rhythm, especially too hastily, which entirely changes the character of these exercises

Unnecessarily fatiguing students through excessive consecutive repetitions of the same exercise, or through repetitions not sufficiently interspersed with walking steps during the field crossing

Failing to regulate the pace of movement, regardless of type; or regulating it poorly—either too hastily or too slowly

Failing to match the overall workout rhythm and the specific rhythm of exercise movements to the students' capabilities

3. Sessions without a Field or in Continuous Line

The field system allows optimal use of limited space when exercising many subjects simultaneously across multiple groups. However, it is possible to conduct a session without using a formal field, provided one respects the principle of movement through space and all other training guidelines.

For example, instead of moving back and forth across the same area, the group progresses in any direction, always moving forward while regulating movement intensity as one would on the field. This approach resembles the wilderness trail session or continuous journey method described below (section 5).

This approach is especially useful when lacking sufficient open space to establish a proper field. It allows for conducting a session along an avenue, path, or any suitable route. It works particularly well with a single group; with multiple groups, leadership and supervision become more challenging than on a formal field.

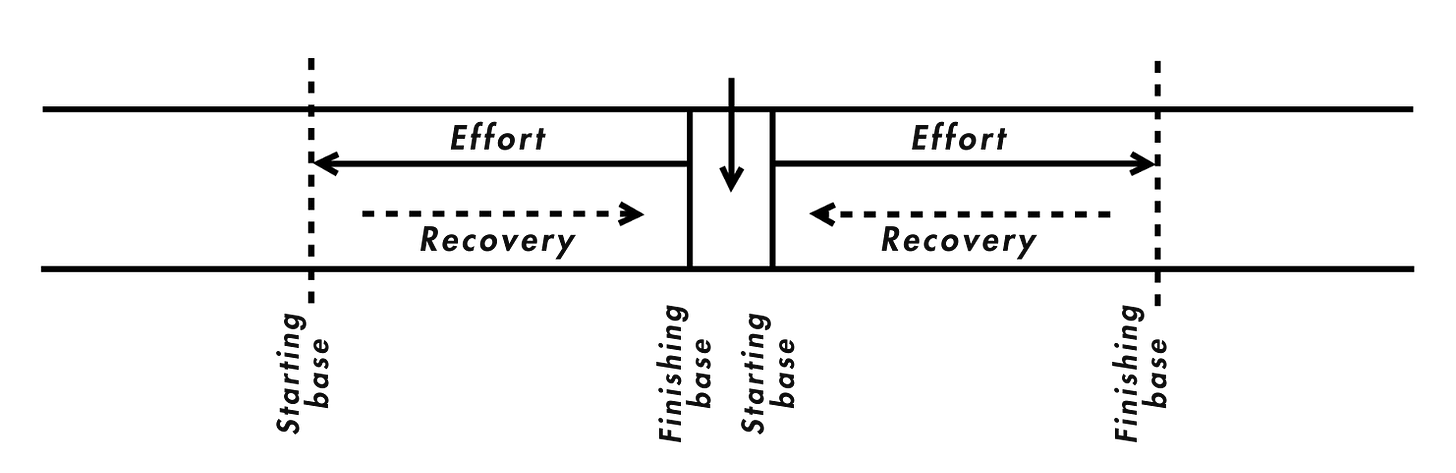

4. The Narrow-Strip Field and the Double Field

On a narrow strip of sufficient length—such as a garden path, trail, passageway, school yard, or even a simple corridor—it remains possible to establish a narrow field and conduct a back-and-forth session applying the wave pattern principle. This simply requires increasing the number of groups (or waves) while reducing each group to only one or two students, depending on available width.

One can even establish a double field lengthwise, or more precisely, two narrow fields one after another, with their starting bases adjacent. The instructor positions himself between these two bases to lead the session. On the two fields thus formed, groups are equally distributed and work simultaneously, but moving in opposite directions.

The double field approach can occasionally be used with standard-sized fields when an instructor finds himself alone, for example, working simultaneously with two different groups of students. Instead of being extensions of one another, the two fields can also be perpendicular or parallel to each other if terrain conditions or practical considerations require it.

5. The Wilderness Trail Session or Continuous Journey

The limited-space field session follows an established plan and takes place with back-and-forth movements. This plan comprises a logically ordered sequence of all the fundamental natural and utilitarian exercise types.

The wilderness session unfolds as a continuous journey across varied terrains featuring diverse obstacles. Some or all natural, utilitarian exercises necessarily form part of its composition. However, neither this composition nor the sequence of exercises can be predetermined; both are dictated by circumstances, the nature of the terrain traversed, and the number and variety of obstacles encountered. The instructor decides which exercises to perform based on the training opportunities presented by the route. For example, he has students cross obstacles, descend or climb slopes, climb trees, scale rocks or walls, lift, carry, or throw stones and other objects.

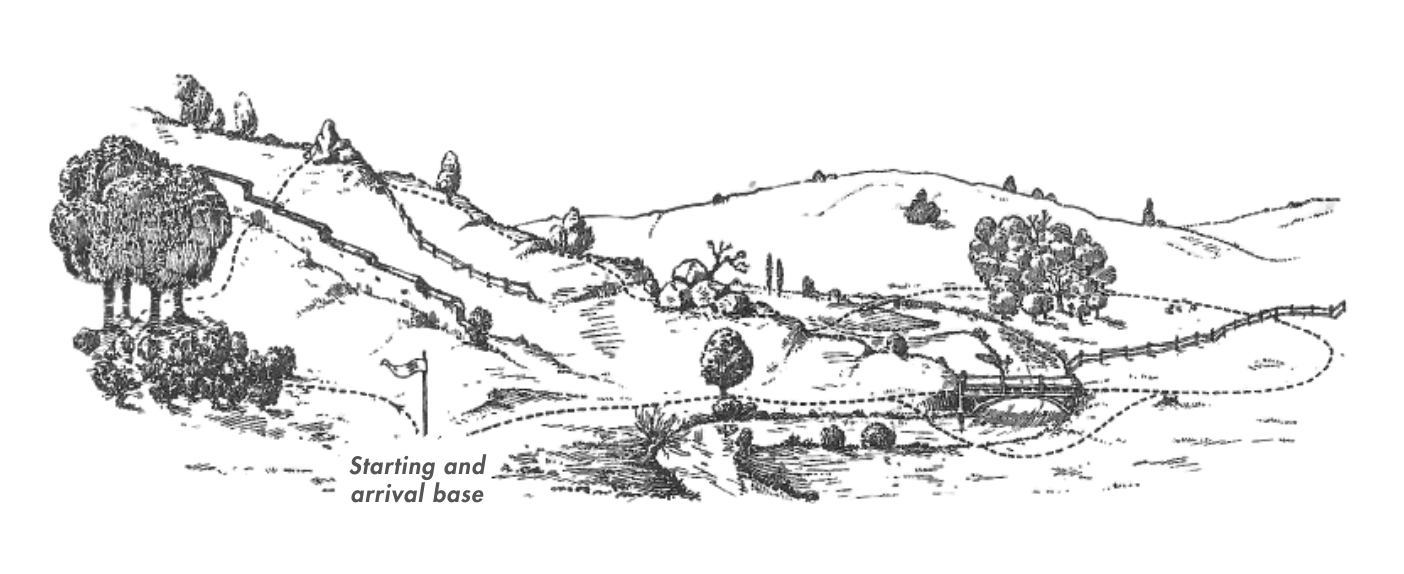

Composing a wilderness session therefore consists not of establishing a sequence of predetermined exercises, but of deciding on a route or itinerary, choosing one that offers the most interest in terms of exercise variety and number.

The wilderness session follows the same working principles as the field session; there is absolute correspondence between the two types of sessions in this regard. However, in the wilderness session, these principles must be adapted to execution conditions different from those of the field session. This adaptation accounts for the following observations:

1. The wilderness session is not a "steeplechase" race to finish first, but rhythmic work. The instructor leads the workout to bring his students to the end in good condition—neither breathless nor exhausted.

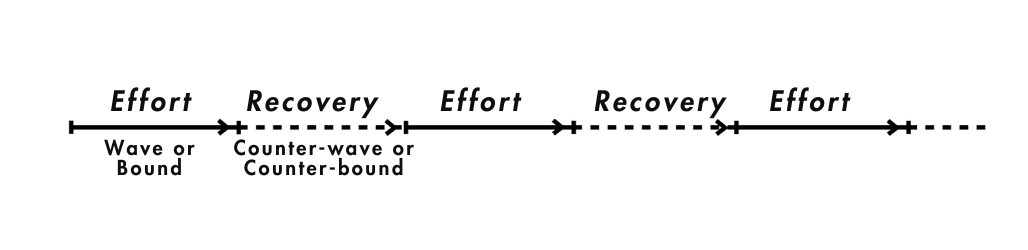

2. The rule of alternation that ensures continuous work on the field while providing the organism with necessary relative rest periods is applied during the wilderness journey through "bounds" and "counter-bounds," whose principle corresponds to that of waves (effort) and counter-waves (recovery).

A bound is a short-distance segment executed at various paces depending on circumstances, in the form of running or walking as well as quadrupedal movement, balancing, climbing, obstacle crossing, or carrying.

Practically speaking, a bound corresponds to the movement or effort performed in a wave across the training field. Its length varies from a few meters to 30 or 40 meters, or much more depending on circumstances. Everything depends on the nature of the ground, its slope, the obstacles present, and the capabilities of the students.

Between successive bounds, students perform slow or moderate-paced walks (counter-bounds), which allow for relaxation or moments of relative rest.

3. During a wilderness journey, each subject enjoys even greater freedom of action regarding effort and recovery than on the field. They can easily prevent fatigue and avoid breathlessness by self-modifying their pace, reducing certain efforts, or mitigating or even circumventing certain difficulties. For example, when facing obstacles too difficult or challenging for their strength or training level, a struggling student may simply "pass over" the obstacle instead of jumping it, or even avoid it with a detour. If they fall behind during a bound, they can always easily make up the distance without needing to push too hard during the slow progression of the counter-bound. They cover the same distance as their more vigorous comrades but with less intense effort, remaining at a lower average speed. The group leader should only signal a new bound when the entire group has reassembled (without stopping the march), just as on the field, he waits for all subjects to reach the starting base.

4. Depending on the type of route, the wilderness session can take the following forms:

Adventurous or on unknown/unplanned routes

On planned or pre-marked routes

On specially organized routes

Finally, mixed sessions can be conducted—performing a short route, then stopping in a clearing, meadow, or suitable terrain to execute, as on a proper training field, certain exercises that movement along the route doesn't allow to be practiced properly.

5. In each group, the instructor or leader has students adopt the formation best suited to the nature of the terrain being crossed. Depending on circumstances, he orders single file, massed formation, or line formation (in wave).

Massed formation is most common and should be adopted without special instruction. The other two formations are used only to facilitate certain passages (single file in defiles), to cross certain obstacles, or to climb slopes as a line, that is, in wave formation.

6. During a wilderness journey, the instructor's role is much more difficult, delicate, and tiring than on the field. First, the instructor must personally complete the route alongside his students. Additionally, general supervision becomes more challenging. Absorbed by leading the whole group, he cannot attend to details as readily as on the field. He benefits from reducing the number of groups to two or even one (if the number of students is small), whereas on the field, increasing group numbers is preferable. Above all, he must be concerned with training good group leaders beforehand to assist during the journey. His position depends partly on the help he can count on. He may be with the first group of the strongest students, with the last group of the weakest, or between two groups. Groups should follow each other at a distance of only a few meters.

7. On a complete stadium, it is possible to mark out a route and conduct a continuous journey session using all the facilities and installations: regular tracks, obstacle courses, climbing structures, etc. Such a session offers certain advantages of outdoor lessons but lacks the unexpected elements and varied difficulties of journeys across diverse terrain. However, such a session serves as useful preparation for outdoor journeys, both for students and instructors.

8. Due to the various difficulties inevitably presented by wilderness journeys, various precautions must be taken by both instructor and students.

Above all, one must remain within the strictly practical domain. This is the primary means of preventing accidents. In the first attempts at wilderness sessions, students—especially young people—are often tempted to "play the fool" and engage in all sorts of potentially dangerous antics or extravagances that risk ending badly. The instructor's role is to anticipate these thoughtless impulses of youth and maintain exercise execution within normal or realistic bounds.

For example, everyone must ensure secure footing. On prepared terrain, this detail matters little. But in the wilderness, one must quickly assess ground conditions and clearly see small obstacles like holes, protruding objects, loose stones, etc., where one risks painful foot twisting or sprains, especially if ankles are naturally weak or poorly trained.

Similarly, one should never blindly launch oneself over an obstacle without quickly assessing its nature and potential dangers. When jumping on a specially prepared jumping pit, one focuses attention solely on the height to clear, without worrying about the takeoff or landing surface, known to be well-prepared in advance. But in the wilderness, conditions differ. The takeoff ground may be very poor and the landing hazardous. Depending on circumstances, the appropriate decision varies: one might directly clear the obstacle, jump or simply climb onto it (if solid and firm), or avoid it by some means.

Finally, tree climbing must be executed cautiously, especially in groups. There is always risk of slipping or losing grip with hands or footing; moreover, branches are not always solid.

9. The wilderness session should be considered a small expedition and, beyond the route to travel and destination to reach, should have a figurative or real purpose which may be, depending on circumstances of time, place, and student age: an exploration; a summit ascent; a hunt or figurative bounty to bring back (flowers, wood, fruit); a mock battle; a rescue or aid mission. A session understood this way fulfills the triple aim of physical education: physical, energetic, and moral development.

2. Common Mistakes to Avoid When Leading Groups on the Field

The main mistakes an instructor must avoid when leading groups are:

Having multiple groups wait motionless at the starting base before launching them across the field (congestion at start due to poor overall pace regulation)

Launching a wave across the field before the previous one has cleared, or will certainly clear, the finishing base (causing congestion and disorder at this base)

Returning along lateral bases at high speed or in a state of muscular and nervous tension

Starting a wave without proper lateral spacing between students

Launching a wave without precise instructions regarding starting position (prepared or not), mode and pace of movement, exercise to be performed, mechanics of execution, repetition or duration

Allowing students in a wave to cross paths, bunch up, zigzag, or jostle each other instead of requiring each to progress exactly straight ahead

Ordering impractical, conventional, or fanciful exercises that serve no useful practical purpose

Having useful exercises repeated with inappropriate rhythm, especially too hurriedly, which completely changes the character of these exercises

Unnecessarily tiring or straining students through too many consecutive repetitions of the same exercise or through repetitions not sufficiently broken up by walking steps while crossing the field

Not regulating movement speeds regardless of type; or regulating them poorly, meaning either too hurriedly or too slowly

Not matching the general work rhythm and specific movement rhythms of exercises to students' capabilities

3. Lessons Without a Field or in Continuous Line

The field system makes optimal use of restricted space when exercising many subjects simultaneously in multiple groups. However, it's possible to conduct a lesson without using a marked field, provided one respects the principle of movement-based work and all other training rules.

For example, instead of moving back and forth over the same area, one progresses in any given direction, always moving forward while regulating movement intensity as one would on a marked field. This approaches the case of the open-country course or continuous route lesson described below (no. 5).

This approach is especially useful when no open space of sufficient size is available for creating a field. It allows conducting a lesson along an alley, avenue, or any path. It works particularly well with a single group to lead; with multiple groups, direction and supervision are more difficult than on a marked field.

4. The Narrow Strip Field and Double Field

On a narrow strip of sufficient length - such as a garden path, walkway, passage, school courtyard, or even a simple corridor - it's still possible to establish a narrow field and conduct a back-and-forth lesson applying the wave principle (principe du travail en vague). One simply needs to increase the number of groups (or waves) while reducing each group to two students or even one, depending on the available width.

One can even establish a double field lengthwise, or more precisely, two narrow fields in succession with adjacent starting bases. The instructor positions themselves between these two bases to conduct the lesson. Groups are equally distributed across the two fields thus formed and move simultaneously but in opposite directions to each other

5. The Open Country Course or Continuous Route Lesson

The restricted-space field lesson has an established plan and is executed with back-and-forth movements. This plan includes a logically ordered sequence of all fundamental types of natural and practical exercises.

The open country lesson unfolds as a continuous journey (en trajet continu) across various terrains more or less furnished with diverse obstacles. All or part of the natural and practical exercises necessarily enter into its composition. However, neither this composition nor the order of exercise execution can be planned in advance; both are dictated by circumstances, the nature of terrain crossed, and the number and variety of obstacles encountered. The instructor decides which exercises to perform based on the training opportunities presented by the route. For example, they might have students cross obstacles, descend or climb slopes, climb trees, scale rocks or walls, lift, carry, or throw stones or other objects...

The composition of an open country lesson therefore consists not of establishing a sequence of predetermined exercises, but of deciding on a route or itinerary and choosing one that's as interesting as possible in terms of the number and variety of exercises possible.

Example of Route for an Countryside Parkour Session

The departure begins toward the left. The route includes first an open space for initial warm-up running; then underbrush for quadrupedal progression; a slope to climb; a wall to scale; a second slope to climb; rocks to traverse; various obstacles (ditch, embankment...) to cross by jumping; a river crossing using balance on a tree trunk; a wooded area where one can perform climbing, lifting, carrying and throwing; a meadow allowing execution of defense exercises; finally an obstacle-free space for return to the starting base, either directly by crossing the river bridge, or after swimming across the river.

The open country lesson follows the same work rules as the field lesson; there is absolute concordance between these two types of lessons from this viewpoint. However, in the open country lesson, these rules must be adapted to execution conditions different from those of the field lesson. This adaptation takes place according to the following observations:

1º The open country lesson is not a "steeplechase" race to see who arrives first, but rather a rhythmic work session. The instructor conducts the work in such a way as to bring their students to the end of the course in good condition - neither out of breath nor exhausted.

2º The rule of alternation that ensures work continuity on the field by providing the organism with necessary relative rest is applied, during the course, through "bounds and counter-bounds" whose principle corresponds to that of waves (effort) and counter-waves (recovery).

A "bound" is a short distance traveled at various paces according to circumstances and can take the form of running or walking as well as quadrupedal movement, balance work, climbing, obstacle crossing, or carrying.

Practically speaking, a bound corresponds to the movement performed or effort given in a wave on the training field. Its length varies from a few meters to 30 or 40 meters, or much more depending on circumstances. Everything depends on the nature of the ground, its slope, the obstacles present, and also the capabilities of the students.

Between successive bounds, slow or moderate-paced walks (counter-bounds) are performed, which allow for relaxation or ensure a moment of relative rest.

3º On a course, each subject possesses even greater freedom of action for effort or recovery than on the field. They can easily prevent fatigue and avoid breathlessness by modifying their own pace, reducing certain efforts, lessening or even avoiding certain difficulties. For example, when faced with obstacles too difficult or demanding for their strength or training level, the struggling student can "pass" the obstacle instead of jumping it, or even avoid it by taking a detour. If, on the other hand, they fall behind during the execution of a bound, they can always easily catch up without having to force themselves during the slow progression of the counter-bound. They cover the same distance as their stronger comrades but by providing less violent efforts, that is, by staying within a lower average speed. The group conductor should only signal for a new bound when the entire group is gathered (without stopping the march), just as they wait on the field for all subjects to arrive at the starting base.

4º Depending on the type of course, the open country lesson can take the following forms:

Adventure-style on unknown or unplanned routes

On planned or pre-marked routes

On specially organized courses

One can also execute mixed lessons - that is, complete a short course, then stop in a clearing, meadow, or suitable terrain to execute, as on a proper training field, certain exercises that movement along a route doesn't allow to be practiced properly.

5º In each group, the instructor or conductor has students take the formation best suited to the nature of the terrain being crossed. Depending on circumstances, they order single file, massed formation, or front formation (en vague).

Massed formation is most common and should be taken without special indication. The other two formations are only employed to facilitate certain passages (single file in narrow passages) or to cross certain obstacles or climb certain slopes as a front, that is, in wave formation.

6º On a course, the instructor's role is much more difficult, delicate, and tiring to execute than on a field. First, the instructor must personally complete the course alongside their students. Additionally, they can less easily maintain general supervision. Absorbed by directing the whole, they cannot attend to details as much as on a field. It's beneficial to reduce the number of groups to two or even one (if the number of students is small), whereas on a field it's preferable to increase them. They must especially concern themselves with forming, beforehand, good group conductors to help during the course. Their position depends partly on the help they can count on. They can be with the first group composed of the strongest, or with the last composed of the weakest, or between two groups. Groups should follow each other at only a few meters' distance.

7º On a complete stadium it's possible to mark out a route and execute a continuous journey lesson using all the amenities and installations: regular tracks, obstacle course, climbing frames... The lesson executed this way offers certain advantages of outdoor lessons, but lacks the unpredictability and full range of difficulties found in varied terrain. However, such a lesson is useful as preparation for outdoor courses, both for students and instructor.

8º Due to the various difficulties inevitably presented by a course in open country, various precautions must be taken by both instructor and students.

Above all, one must stay within strictly practical limits. This is the main way to prevent accidents. In their first attempts at open country lessons, students, especially young people, are often tempted to "act foolishly" and engage in all sorts of dangerous fantasies or extravagances that risk ending badly. The instructor's role is to anticipate these thoughtless enthusiasms of youth and keep exercise execution within normal or reasonable bounds.

For example, everyone must watch their foot placement carefully. On prepared terrain, this detail doesn't matter. But in open country, one must quickly assess ground conditions and clearly see small obstacles such as: holes, protruding objects, loose stones, etc. where one risks a painful foot twist or even a sprain, especially if ankles are naturally weak or poorly trained.

Similarly, one should never blindly launch oneself over an obstacle to be crossed by jumping without quickly recognizing its nature or dangers it might present. To execute a jump on a specially prepared jumping area, one concentrates attention solely on the height to be cleared, without worrying about takeoff or landing ground known to be well-prepared in advance. But in open country it's not the same. The takeoff ground may be very poor, and the landing ground dangerous. Depending on circumstances, the decision differs; one either crosses the obstacle directly, jumps or simply climbs onto it (if it's solid and firm), or avoids it by some means.

Finally, tree climbing must be executed with caution, especially in groups. There's always risk of slipping or losing hand or foot holds; moreover, branches aren't always solid.

9º The open country lesson should be considered as a small expedition and, beyond the route to be covered and destination to reach, have a figurative or real purpose which, depending on circumstances of time, place, and age of students, might be:

An exploration

A climb

A hunt or figurative bounty to bring back (flowers, wood, fruits)

A mock battle

A rescue or aid mission

The lesson conceived this way serves the triple aim to be pursued in physical education: physical, virile, and moral.

La Méthode Naturelle Series - Previous Installments

Chapter 1: Principles of Natural Movement

Principles of Natural Training (Sections 1-3)

The Proper Training Session (Sections 4-6)

The Lost Art of Relaxation (Sections 7-12)

Finding the Sweet Spot (Sections 13-17)

Rigor + Nature = Vigor (Sections 21-26)

Strength in Song (Sections 27-33)

Chapter 2: Conducting the Lesson

The Wave Pattern Principle (Section 1)

I haven't noticed any mention of Philippe's translations. Have you forgotten his books that I gave you?