This is part 7 of an ongoing series bringing the Georges Hébert’s “Natural Method” training protocols to an English-speaking audience for the first time. In this installment, I present sections 21 - 26 of Chapter 1: Principles of Natural Movement – dealing with the topics of duration, frequency, ordering of exercise, group size, skin care, and evaluations. First is my commentary. If you just want to read the translation, you can skip ahead.

“Natural movement” has an image problem. When I try to explain to normal people what we do at the Natural Outdoor Workout (“Climbing, crawling, barefoot running… you know, the full spectrum of natural human movements!”), I think they have a certain image in their head.

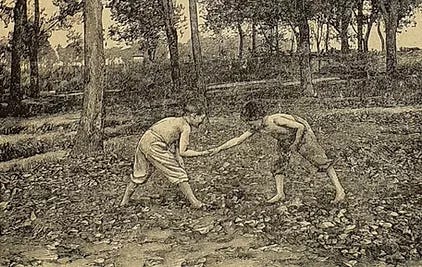

Wildly running about on all fours. Hanging upside down from trees. Rolling around in the dirt. Total chaos.

And they’re not completely wrong to imagine this.

However, when you go back to the original instructors’ training manual for La Methode Naturelle, Georges Hébert paints a very different picture of the perfect workout.

This week’s installment of his Concise Guide for Trainers continues to lay out the structure of the workout – from ideal duration, to frequency and group size, along with protocols for tracking subjects’ progress. Every detail is thought out and planned in advance, so that participants will get the greatest benefits out of a time-limited session (20 minutes to 1 hour max).

Where some people might see a paradox, I see a perfect harmony in Hebert’s work between structure and freedom—tension and relaxation—both in the movements themselves and in the design of natural movement workouts.

To understand his perspective, it helps to have some context on the environment in France in Hebert’s era (early 20th century). Section 23 below gives a hint, when it refers to the “Cartonian objective indices” of vitality, which Hebert used to rank training subjects and properly “dose” workouts. I had to look up these Cartonian indices, and information is scant, but the concept comes from a naturopathic physician – Dr. Paul Carton – who was a contemporary and friend of Hébert’s.

Dr. Carton was a leader in the early 20th century “naturist” movement. Naturists advocated healthy living through natural foods (often vegetarian), loose-fitting clothing, avoiding intoxicants, and engaging in frequent, vigorous, outdoor activity. At a time when medicine struggled to explain or cure many diseases, naturists observed that industrial cities, restrictive clothing, processed foods, and oppressive work all contributed to poor health. During World War I, Hébert had observed that indigenous island peoples who lived and worked outdoors were generally vital and agile, and mostly free of modern illnesses – without anything like “dieting” or “exercise”. He aimed to imbue urban populations with this vigor without sacrificing the benefits of civilization. Hence, la Methode Naturelle was born.

Dr. Carton developed objective health “indices” like pulse rate and chest to height ratio, which Hébert used to gauge students' fitness levels and group them accordingly. Though rooted in the principles of nature, the methods for recovering our natural fitness require rigor and structure. Hebert’s system has both—planned timing, order, specific durations, commands to start and stop, etc. Progress is quantified through fitness records to help with motivation. There is always freedom of movement, but it’s contained within a rigorous and disciplined framework.

Unlike later offshoots of naturism (think “dirty hippies”), Hébert also emphasized hygiene through rigorous skin scrubbing following an outdoor workout. For Hébert, hygiene didn’t mean a leisurely spa treatments. It was about friction—vigorous scrubbing, and contact with fresh air and open water. For what it’s worth, I never feel cleaner than when I emerge from the frigid and murky Bay waters. My skin feels crisp, and my lungs feel supple. Following Hébert, I’ve also taken to “exfoliating” by vigorously rubbing wet sand into my skin.

Today, too much training takes place in climate-controlled gyms under artificial lights. Exercise machines and treadmills dictate rigid movement, yet most of the time we just wander aimlessly from one machine to the next with no one to guide us. It’s the precise opposite of Hébert’s system, in which instructors are there to structure the outdoor workout for maximum freedom of movement.

It’s also worth noting that he does not recommend these general training sessions all year round. For those who are already in shape, he says, only a few weeks per year of intensive general training are necessary. Once you reach this baseline, you can get on with other sports or specialized training, periodically refreshing your fitness with brief “bootcamps” of a few weeks, working out 3 or 4 times per week. For those who are out of shape, he recommends training maybe 15 weeks out of the year, 4 days per week, until greater fitness is achieved. I wonder if more people would consider adopting a fitness routine if they knew they could get the benefits by working out just 1 week out of every six.

I’m still trying to find the right balance between structure and freedom in my local natural movement meetup group. The Concise Guide gives a glimpse of what the real thing looks like—something for me to aspire to. If you're local, you can join the Natural Outdoor Workouts every Saturday morning near the Berkeley Marina. We welcome all levels of movers, and try to provide enough structure while accommodating everyone’s limitations.

I’m planning to schedule one session each month modeled directly on the protocol Hébert lays out.

And now, here’s Hébert:

21. Annual workout program. Duration and frequency of weekly sessions.

A short session lasts less than 20 minutes; a medium session lasts 20 to 30 minutes; finally a long session lasts 30 to 45 minutes or 1 hour at most.

The number of sessions to be held per week is one to two at minimum, three to four on average, and five at most. Two rest days without training, preferably consecutive, are necessary for organic recovery.

The period of annual general training is 2 to 3 weeks minimum for subjects already developed and regularly practicing varied sports; 4 to 6 weeks on average; 12 to 16 weeks at most, assuming an average of three to four sessions per week. If the number of weekly sessions is more limited, the number of weeks should be increased accordingly.

The rest of the year is reserved for learning and technical refinement of various exercises (especially swimming during the favorable season), full-scale games, sports, specialized training, long hikes and cross-country races, diverse locomotive activities (on bicycle, horseback, skates, skis, rowboats, etc.), but with periodic resumption of general training exercises, in order to maintain abilities and not lose ground.

22. Specific order and duration of implementation

There is no single defined order for the successive execution of the exercises that make up the session.

The best order is one that, by alternating the fundamental families of walking, running, jumping, etc., and within each family, by alternating the various types of exercises that compose it, ensures the continuity of the workout without exhibiting any objective signs of fatigue. A planned order can moreover change during the session if circumstances or the students' state of fatigue require it. The order indicated below regarding durations is one of the most practical with respect to alternating families.

The specific amount of time allotted to each type of exercise varies considerably. On one hand, it depends on the relative importance of that exercise compared to the others in the session. On the other hand, it is always limited by the need to provide the body relief by switching to another form of activity. In essence, the duration acts as a way for the instructor to properly dose the exertion across the different exercise families. If one particular type of exercise is prolonged unnecessarily, it reduces the time available for the other types of exercises. This can disrupt the flow of the rest of the session, or lead to premature fatigue. So the instructor must carefully balance the time allotted to each exercise based on its purpose in the training, while providing the trainee time to recover through variation.

As an example, the following average durations can be allotted for a 40-minute session:

Sprints and walking (warmup) - 4 minutes

Quadrupedal - 4 minutes

Climb - 5 minutes

Jump - 5 minutes

Balance - 4 minutes

Lever - 3 minutes

Throw - 5 minutes

Self Defense - 3 minutes

Timed Course - 5 minutes

Slow walk to cool down - 2 minutes

23. Group sizes and ability levels. Ranking students.

A single instructor can manage a maximum of 30 to 40 children or adolescents, and only 24 to 30 young people or adults. The ideal average size is 20 to 24 subjects.

For any enrollment of more than six students, it is divided into several groups of approximately equal size. The ideal number of groups for the workout is four or more. The first group comprises the strongest subjects, the last group consists of the weakest subjects, and the intermediate groups are made up of subjects with medium ability.

To make sessions as effective as possible, the ranking and division of students among the groups should take into account the following:

medical information concerning the weaknesses of certain subjects;

the performance on tests measuring the overall physical fitness; or, lacking those results, the results of a visual examination of abilities by the use of certain fitness criteria.

Ideally you can adjust these indicators according to the innate robustness and intrinsic vitality according to the Cartonian objective indices.

24. Commanding exercises and leading groups.

The instructor has the freedom to control exercises, that is, to optimally order their initiation or their cessation. In natural pedagogy, these are not “commands” in the sense of military training, which result in rigid and subpar execution.

A command is merely a designation of the exercise to be performed, followed by an initial signal to attract attention, and then a pronounced follow-up to signal the start. This start, of course, is collective (i.e., made in unison), but each person immediately regains his freedom of movement and works at the rhythm that suits him best. Thus synchronization is impossible.

The designation of the exercise must be made brief but clear. In addition, the instructor can inform students in advance of any conventions or shortcuts he deems useful. What matters is the precise, smooth, and time-consuming agreement between the instructor and his students.

Examples of short-cut designations of exercises and commands include:

Run in a straight line (implied: departure): “In position! Go!”

Run with half-turns (implied: right or left) In this exercise the half-turns to the right or the left are made during the course of the run at the direction of the instructor: “Right!” for the right turn, or “Left!” for the left turn.

Two-handed throwing (underside Tender With lower and upper trunk). “In position!” (implied: widen the stance and take the throwing ball in both hands). The juggling begins at the injunction: “Juggle!” or “Go!” Or, if the instructor wants to specify the various movements (especially for learning with beginners), he makes the following injunctions: Up! (raise your arms). Down! (lower the trunk and arms). Start! (throw the ball forward in the air by straightening the trunk). Catch! (run forward to catch the ball in both hands).

Exercise terminations are carried out at the orders of “Stop!” or “Cease!” In some cases, these directives may apply only to the primary exercise. For example: for a throwing exercise that involves running forward, the injunction “Stop!” may mean stopping the throwing, but not the moving forward.

25. Skin conditioning.

Airbaths, sun baths, as well as rain baths are the first and best skin conditioning. Additional skin conditioning after the session, just before the dressing, consists of:

general or partial washings followed or not by scrubbing;

wet scrubbing with a towel, sponge, or best of all, with the palm of wet hands, on the legs, arms, lower back, neck, chest and abdomen;

dry scrubbing with a washcloth, a pencil glove or just palm of hands.

Scrub the limbs strongly toward the trunk and very weakly in the opposite direction.

26. Evaluating Results. Fitness Records. Competitions.

To effectively direct training, it is necessary to identify weaknesses in the trainees and to periodically assess their progress.

For this purpose, each student should have a fitness record for the various types of exercises. This record is created in the first week of baseline training and renewed at set intervals. It documents the performance executed across all kinds of tests: runs, jumps, climbing, lifting, throwing, swimming, etc.

Creating these fitness records gives rise to and sustains a real self-emulation among adolescents and especially young adults, which benefits their training through the idea of competing against oneself. But for this to happen, the trainees must possess a copy of their own record. When the results of the tests are handy, everyone is interested in their performance and seeks to improve it, especially after initial progress has been made.

Furthermore, in order to develop or maintain the competition between students themselves, both performance tests as well as group or individual competitions should be organized at the end of the training period.

These competitions should include tests of a variety of different natural and practical exercises, to provide both an opportunity for observation and a benchmark for general training.

They can take place as separate events, with scored and quantified performances, with the ranking of the subjects determined by the number of points obtained. Or more simply, they can take place on a course of determined length and scattered with obstacles of all kinds: ditches and embankments to jump over, barriers, walls or trees to climb. At certain points along the course are a set number of objects to throw or bags to carry; finally, crossing a stream or swimming pool can complete the circuit.

In this latter case, the ranking of the subjects is determined by the order of arrival at the finish or the time taken to complete the course.