This 40-day Lenten fasting challenge begins this Sunday (2/26), with the setting of your first weekly rule. The aim is to gradually increase the duration of your daily fast, toward the recovery of the traditional practice of eating just one meal a day.

Each week, I’ll provide more context and resources to help you stick with your chosen fasting rule. Please email me any feedback on the templates or content.

Intermittent fasting is making a comeback. One variation, “OMAD,” is particularly popular among busy professionals since it involves eating just One Meal a Day (hence the acronym).

Some have labeled it a dangerous fad – or even a starvation diet – but even a brief examination of the topic reveals that restricting when you eat rather than how much is one of the safest, most effective forms of dietary discipline. The health benefits go far beyond simply losing weight, to promoting a more efficient metabolism and clearing out the junk proteins that normally accumulate in our cells.

You wouldn’t know it from reading the secular literature, but the practice of eating only one meal is an ancient discipline – dating back to early Christianity and Judaism before that. Indeed, there is nothing new under the sun.

In the early Christian Church, Wednesday and Friday were considered fasting days – meaning that disciples would not eat from dinner the night before until at least 3 pm on the fasting day. This tradition was updated from the even older Jewish practice of twice-a-week fasting on Mondays and Thursdays, in addition to certain Holy Days.

Some Catholics still abstain from meat on Fridays year-round, and the Eastern Orthodox Church is known for the numerous strict abstinences that are recommended during fasting seasons such as Lent and Advent. The idea of a spiritual rule of fasting, however, has fallen out of favor – especially in the West.

In today’s Catholic Church, there are only two mandatory fasting days: Ash Wednesday and Good Friday. These days are the bookends for the 40-day penitential period of Lent, which culminates in a feast on Easter Sunday. On these fasting days, Canon law prescribes just a single meal, but makes allowance for two “collations” or small meals that do not add up to a full-sized meal.

As the fasting requirements have lessened, so too have the physiological benefits. Secular people are rediscovering the benefits of fasting with urgency, in light of the obesity and diabetes epidemics.

Catholics in particular, however, should be asking what they can gain both spiritually and physically from recovering their own ancient tradition of One Meal a Day fasting.

St. Benedict and the One Meal

“The principle of just one meal… is the essence of the fast.” – Adalbert de Vogue, OSB, To Love Fasting

As I mentioned in the previous post, Saint Benedict of Nursia is considered the founder of Western monasticism. The Order of St. Benedict was instituted as a way of preserving the faith at a time when Roman civilization was being sieged by the “barbarians at the gate.” St. Benedict believed that monastic communities had to be governed by a uniform rule to ensure that monks wouldn’t simply free-ride off of the communal living arrangement. In addition to rigorous prayer and self-denial, he institutionalized a fasting requirement as part of his broader Rule for Monasteries as a way of establishing order during such chaotic and perilous times.

The fasting rule was simple. The monks were to eat just one meal a day for 200+ days out of the year – from the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, in September, until Easter in April. During the summer months, a second meal was added to support a longer work day.

The rule of St. Benedict also barred the eating of four-legged animals (i.e., beef, pork, lamb, etc.) year-round. During Lent, monks abstained from other kinds of meat (except fish), and sometimes added additional penances at the discretion of the Abbot. Beyond this, Benedict simply urged the monks to “love fasting” (Jejunium amare).

The full line from Chapter 4 of the rule states:

“Renounce yourself in order to follow Christ; discipline your body, do not pamper yourself, but love fasting.”

While most of us find this command at odds with our natural appetites, it was embraced by the devout early Christians and Desert Fathers and Mothers who discovered that fasting allowed them a closer union with Christ.

Paradoxically, it is by not eating that these holy men and women learned to satisfy their deeper hunger with the “supersubstantial bread” that Christ offers in abundance to those who ask through the Lord’s Prayer:

"Give us this day our daily (epiouision) bread."

For centuries, this spiritual understanding accompanied the practice of eating one meal on fasting days. The tradition continued through the Benedictine monasteries into Europe during the middle ages. The practice of rigorous fasting during Lent eventually spread to all Medieval Europeans who belonged to the faith – not just the monks. By the 700s AD—some 200 years after the founding of the Benedictines—the standard Lenten discipline in Roman Catholic Europe was even more strict than the original Rule of St. Benedict. It included:

No animal meats or fats

No eggs or dairy

No sexual intercourse between spouses

And no Sundays off.

Fish was permitted, as were wine and beer, but only within the confines of the One Meal a Day tradition inherited from St. Benedict and his predecessors.

Excessive Abstinence & the Decline of OMAD

At some point in the middle ages, the spiritual essence of fasting was lost, along with the principle of the one meal with it.

Taylor Marshall marks the beginning of the decline around the year 800 AD, when the monasteries moved the mid-afternoon nones service to 12 pm, so they could break their fast three hours earlier. Soon after, German bishops began to allow the consumption of dairy or “lacticinia” during Lent in exchange for payment or good deeds. When coffee and tea became widely available, consumption was allowed prior to nones.

The final nail in the coffin came in 1966, when Pope Paul VI limited mandatory fasting to just two days of the year – Ash Wednesday and Good Friday – during which one meal and two collations were also permitted.

Clearly, fasting requirements didn’t erode overnight, so it’s hard to pinpoint what caused this gradual degradation.

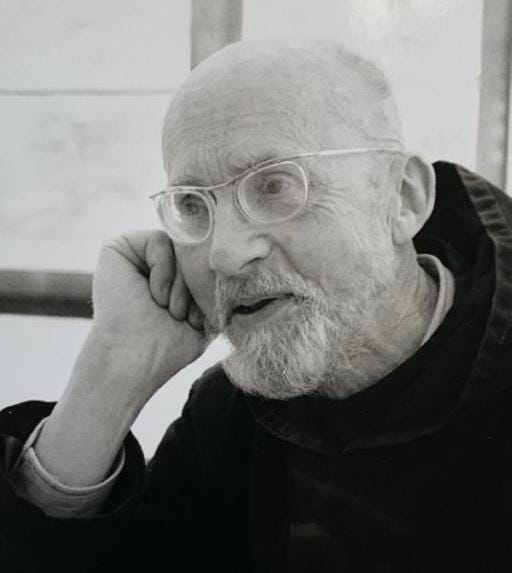

Adalbert de Vogüé was a French Benedictine monk born in 1924 who lived to be 87 years old, passing away in 2011. de Vogüé was Puzzled by his own order’s failure to follow the rule laid out by its founder – the Master – St. Benedict himself. In his book To Love Fasting: The Monastic Experience, de Vogüé examines several explanations for the erosion of the fasting tradition.

Ultimately, he concludes that “Christian fasting has disappeared because pastors and faithful have not reinvented it together in each generation.”

In other words, the original spirit of fasting has been lost. Fasting came to be viewed as purely a penalty, for which other sacrifices could be substituted. In his historical survey of fasting in the church, de Vogüé finds again and again that monks were happy to trade an earlier breakfast for stricter abstinences and lower quality food. One French Trappist community, for example, took the logic of substitutable sacrifice to the extreme by attempting the most severe imaginable abstinences during Lent. The monks were allowed to eat breakfast and lunch, but all of the meals consisted of blackened bread and moldy cabbage. The majority of monks became too ill to complete the 40-day period and had to loosen their discipline just to make it out of the infirmary alive.

“Conceived as a punishment, or at best as a sacrifice, it was particularly exposed to danger in an age when the sense of sin was going to grow feeble, in which the fear of God's justice would yield more and more to a quasi-exclusive accent on his goodness.”

Adalbert de Vogue, OSB. To Love Fasting: The Monastic Experience

In this anecdote, we can hear the echoes of the same “diet culture” that pervades the modern world. People would rather restrict what they eat to a few unappetizing foods than limit when they eat through disciplined fasting, followed by sufficient nourishment in a single, evening meal.

Once the transformation from vital discipline to penal sacrifice had been made, it was only a matter of time before fasting would disappear along with all of the other excessive medieval penances: self-flagellation, chastity belts, and the like. Many of today’s religious leaders still operate on the misguided association of fasting with punishment, and therefore hesitate to make demands on their flock out of fear that they will make God out to be a tyrant.

Recovering the Joy of Daily Fasting

In reviving the Master’s dictum to “love fasting,” de Vogüé attempted to recover the joyful component of the traditional fasting discipline, as he experienced it in the second half of his own life. To love fasting is to flip the whole idea of repentance on its head. It’s not about proud flagellation or a triumph of the will in exceeding our limits. Instead, fasting repentance is about turning away from self-will. It requires a humble surrender to the light yoke of Christ, while discovering what we can do through grace.

Alexander Schmemann, the influential Eastern Orthodox priest, writes that fasting requires “a total effort of our being.” He continues:

“The Orthodox idea of fasting is first of all that of an ascetical effort. It is the effort to subdue the physical, the fleshly man to the spiritual one, the ‘natural’ to the ‘supernatural.’”

In other words, the fasting discipline gives us mastery over ourselves and restores the whole person to what they are meant to be. In fact, the Church Fathers believed that the soul was disordered – not the body – and that asceticism could re-orient the heart’s desires and renew the soul. We must periodically forego even good things, that our bodies need, in order that we may delight in them all the more.

de Vogüé settled on a daily routine of OMAD (long before it was trendy) because he ultimately found it more pleasurable and rewarding than breaking his fast too early in the day, and becoming sluggish. Carving out the freedom to skip breakfast and lunch turned out to be quite difficult for him. Following the modern trend, his superiors actively discouraged fasting in the name of preserving community meals. Eventually, however, de Vogüé was allowed to live as a hermit, and eat only one evening meal each day – in solitude – following the community prayer of Vespers.

After a short adjustment period, de Vogüé found that St. Benedict’s fasting rule was a light burden.

“My mind is at its most lucid, my body vigorous and well-disposed, my heart light and full of joy,” he reports feeling at the end of his daily fast.

Those of us who have dabbled in intermittent fasting can attest to its benefits: mental clarity, surprising new vigor, and even inexplicable joy. We know that neurotransmitters like epinephrine and norepinephrine are activated during fasting, but we should be wary of trying to reduce the fundamentally spiritual nature of fasting to mere physical and chemical reactions in the brain and body.

The Biblical View of Fasting

While it’s true that scripture occasionally refers to fasting as a penitential practice, it is more often framed as a preparation for an encounter with God. To be in the right mindset for this encounter, one must undergo a period of spiritual and physical affliction.

In his book Fasting: The Ancient Practices, Scott McKnight looks at the full Biblical sweep of fasting, and finds that “every dramatic circumstance calls for supplication reinforced by fasting.”

In Lent, Christian disciples fast for 40 days to prepare for Easter. Moses fasted for 40 days and 40 nights when he went up the mountain to meet God in the Burning Bush. He fasts again before receiving the 10 Commandments. The Israelites wandered in the desert for 40 years, subsisting only on Manna, in preparation for their arrival in the land of Milk and Honey.

In the Book of Kings, Elijah fasts for 40 days and nights in order to be able to hear God’s still small voice on Mount Horeb.

And finally, in the New Testament, Jesus fasts for 40 days in the desert in preparation for his public ministry. There, Satan tempts him with an all-you-can-eat buffet of bread, to which he responds, “Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds out of the mouth of God.”

Hearing the word of God, in turn, requires attention. Fasting hones our attentive faculties and temporarily halts the usual bombardment of our senses for long enough to hear what we otherwise might ignore or miss altogether.

If you view fasting as pure penance, you likely will not experience the same degree of preparation. Nor will you be as likely to keep the practice when it becomes difficult. If instead, you view it as a discipline that will help you discern your highest calling, even the periods of difficulty will come with a certain sweetness.

“The regular fast is always possible to one who wants it,” writes de Vogüé, “and is impossible to the one who does not want it.”

The experience of the middle ages should teach us not to stack up too many complicated abstinences, or deprive ourselves too suddenly, when we are seeking to build a keepable habit of fasting. Attempting to exceed our limitations is a kind of perverse pride. However, the resurgence of intermittent fasting, and joyful testimonials of spiritual men like Adalbert de Vogüé, show us that we are still capable of the ancient discipline of eating one meal a day. If we approach this challenge gradually, and with trusting humility, we will discover that it is possible to not just endure fasting, but to love it.

Starting this Sunday, I invite you to set your own keepable fasting rule using my template, or writing down a clear intention on a blank piece of paper: