Calisthenics 101 - From Dad Bod to Greek God, Pt. 3

Breaking through strength plateaus using ancient secrets of bodyweight exercise

Read part 1 and part 2 of this series.

“Do what you can, with what you have, where you are.” – Theodore Roosevelt

Last year, I hit a dispiriting strength plateau. After years of gradual improvement, I found it more difficult to physically “level up.” Was I just getting old? Guys like Art DeVany and Mark Sisson show that you can be extremely fit at any age. Googling around for answers, it turns out most people who deliberately set out to get stronger hit a plateau sooner or later, at which point you either have to work harder, get smarter, or both.

Getting a gym membership would have added a chore—and an expense—to an already-busy schedule. So instead, I turned to the Ancient Greeks, who achieved their ideal of harmonious physical proportions through the art of calisthenics.

The word calisthenics comes from the roots kalos and sthenos. Kalos (κάλλος) refers to the beauty of an aesthetically-pleasing physical form—as in Kalokagathia. Sthenos (σθένος) means strength—physical, mental, and emotional. For the Greeks, exercise was a discipline. Excellence (arête) was the objective, and it was cultivated over a lifetime of practice.

The specific techniques of the Grecian athletes have mostly been lost to history, but calisthenics is still a popular genre. I read every (free) ebook I could find on building muscle with bodyweight exercises. Then, I applied the tips they shared in common. I also took before and after body measurements to see if I was making progress toward the so-called “Grecian Ideal” proportions, based on the Golden Ratio and the statues of antiquity.

After six weeks of calisthenics training, here were my results:

The last 10-20% will undoubtedly be the hardest, but the yellow column shows my improvements in 5 out of 6 areas. The right-most column is the percentage of the “ideal.” These metrics can only approximate strength, but they function as proxies for harmonious physical development. Ironically, today’s bodybuilders go way beyond the ideal proportions, which might be why most people think they look freakish compared to classical and Renaissance statues depicting the old Grecian ideal.

There are infinite how-to videos on different calisthenics exercises and their proper form—I’ll leave that for the YouTubers. In what follows, I have attempted to distill the principles for powering through plateaus and getting the most out of whatever time and effort you dedicate to working out.

1. Simplicity is the ultimate virtue.

“Beauty of style and harmony and grace and good rhythm depend on simplicity.” – Plato

Calisthenics differs from weight lifting in that mostly uses the resistance supplied by one’s own body weight under gravity. It can be practiced anywhere: at home, in the office, in the park, the gym, or even in a prison cell. Think pushups, pull-ups, rows, squats, dips, lunges, planks, and the like.

Complicated lifts and weightlifting routines that isolate specific muscles may be a shortcut to bigger muscles, but they rarely produce the harmony of a simple calisthenics practice, skillfully honed over a lifetime. Simple does not mean simplistic.

Calisthenics naturally leads to harmonious proportions since it requires the whole body to fire in order to add stability to your frame while performing exercises. It also produces fewer injuries, since the forces on our ligaments and tendons are generally limited by our own body weight. However, these limits on force do not limit the potential for generating tension, and strength ultimately comes from increasing tension.

In the Naked Warrior, legendary strength coach Pavel Tsatsouline lays out a dead-simple program for building strength with just two exercises: the one-legged pushup and the one-armed pushup. His reasoning is that most people who get to an initial strength plateau can do dozens of repetitions of common exercises like the pushup or bodyweight squat. You might eventually hit failure because of the metabolic stress and build-up of lactic acid, but doing 100 squats or 60 pushups in a row never puts the muscles under high enough tension to get stronger. You have to increase the difficulty somehow.

This is where skill comes into play.

2. Strength is a Skill.

Weight lifting may be the easiest way to increase muscular tension. More plates = more weight. However, weight is only one factor that influences tension. You can also add tension through conscious and deliberate muscle contraction. Contracting the right muscles, at the right time, with the right amount of tension constitutes the primary skill of calisthenics.

Strength comes from tensing muscles harder, not exhausting them with countless reps. You can learn to contract harder by developing a tighter mind-to-muscle connection (MMC). Anthony Arvanitakis writes: “If your body is the barbell you lift during a bodyweight workout, MMC techniques are the way you can mentally add more weight onto that barbell.”

Neuromuscular tension control also allows for greater stability throughout a range of motion. Muscle growth is a byproduct of increasing tension control with stability. For example, if you are performing pushups, you might slow down your movement and tense your chest as you go down – visualizing that you are pushing through thick molasses. As you gain more mastery over your body, you will be able to shift more of your body weight (and thus gravitational force) from your feet to your hands. You can see the extreme version of MMC in the strongman “Hand to Hand” act, where a single hand acts as the sole point of support. The rest of the body must tense up to create stability through the movement.

This is why calisthenics emphasizes perfection of form throughout movements over mindless heaving and grunting.

3. Maximize Tension, not Reps.

Pavel Tsatsouline provides these five conditions of high tension for his chosen bodyweight exercises:

Significant external resistance

Application of high tension and power breathing techniques

Limiting repetitions to 5 per set or less

Approaching each set relatively fresh

Moving fairly slow

For hardcore fitness people, the hardest part about this system is that 5 reps per set can feel ‘too easy.’ Citing Russian sports scientists, however, Pavel says that maximum strength comes not from going to failure but stopping well short of it. Instead, he suggests “greasing the groove” i.e., performing frequent, low reps at high tension, with lots of rest in between. The Grease the Groove technique is about adapting the nerves—turning them into superconductors—such that they are capable of producing far more work than you typically ask of them in daily training.

External resistance in the Naked Warrior framework comes from your body’s weight being supported entirely or mostly by a single appendage during the one-armed pushup or one-legged squat.

High-tension techniques include tensing the whole chain of muscles from your fingers and palm, through the arm, shoulder, core, into the glutes, legs, and even feet. Here, Pavel offers a colorful image of squeezing a coin between your glutes. In the pushup position, you might flex your free hand behind your back into a tight fist.

The skill of Power Breathing is about creating compression in the body—especially in the thoracic/abdomen, where inflating your lungs roughly 75% generates even more tension and thus power. Martial artists learn to compress that air within their core, and deploy it outward where it’s needed. Pavel likens the arm or leg doing the pushing to a pneumatic lever, and suggests picturing a long deflated balloon (like the ones that clowns shape into dogs and hats) inside the bent limb. Then, as you channel the compressed air from your abdomen outward into the arm or leg, you inflate the balloon as you push up. This works!

Some people mistake compression for the exhale itself, watching fighters who make a small “Pfft” sound when they strike. But it’s not the exhale itself generating compression—the mini-exhale is merely a side effect of lots of compression. Russian Systema experts are particularly adept at using this technique to absorb blows and add force to their punches and kicks.

In summary, you are generating a power wave throughout the body. Any links in the chain will cause you to fail. If you can’t do a movement with good form, you should begin with an easier progression that requires less technique to get stronger first. Strong First, incidentally, is the name of Pavel’s company. You can learn more about his philosophy of strength-building in this relatively short Joe Rogan podcast (i.e., it’s only 2 hours).

4. Start with Quantitative Progression

Greek myth purports that ancient strongman Milo of Croton carried a calf up a hill every day until it became a full-sized bull, which has become the go-to metaphor for the concept of progressive overload—expanding your muscles’ limits by increasing the loads almost imperceptibly.

However, before you attempt to copy Milo’s feat, Pavel explains that so-called “progressive overload” only works when you have time to stay at a certain weight below your maximum for an extended period before upping the weight again. This is how the Russians trained during their Golden Era of Olympic lifting. Do you really want to argue with the Russians?

Though he praises calisthenics for its simplicity, Pavel notes that there is no substitute for adding plates to a barbell if you’re trying to build as much body mass as possible. In calisthenics, however, you generate progressive overload by increasing the difficulty of the exercise (i.e., changing the angles of the pushup), or progressing how long those muscles can hold that amount of tension.

5. Limit Frequency OR Intensity

“Keep your training frequency such that you experience more days above baseline than below baseline.” – Michael Allen Smith

When it comes to the ideal volume and idea of “training to failure,” there is quite a bit of controversy and contradictory information—even in the realm of calisthenics. Some recommend training hard, infrequently, while others suggest training as frequently as possible but never pushing to the point of Momentary Muscular Failure.

There is, however, broad agreement that optimal results don’t come from training hard every day. After a workout, muscles are broken down and need time to heal. Testosterone falls during this catabolic period. If you train too frequently, testosterone never gets a chance to fully rebound. Unless you’re using steroids to speed up that recovery process, you need at least a day or so to regenerate before training the same muscle group hard.

Doug McGuff’s Body by Science suggests training once a week, pushing each of the “Big 5” muscle groups to failure through slow, continuous contraction over 90 seconds each. This generates a “minimum effective dose” in a time-efficient way, and also allows plenty of recovery time.

Pavel Tsatsouline and Art DeVany argue that training to failure sets you up to fail—even if only psychologically. In my experience, training to failure too often makes me sore and dampens my energy and motivation in the days following. Pavel’s formula is to train frequently, with heavy weight (high tension), low reps, and plenty of recovery in between (i.e., 5 minutes minimum—15 is better). If you’re working out in the gym, that means rotating between a few different exercises to provide full recovery between sets. I prefer doing micro-calisthenics-workouts at home between work. You can achieve a high degree of neuromuscular improvement through the frequency of repetition, and you don’t get as sore since you’re never going completely to failure.

Pavel’s famous 5x5 workout refers to 5 sets of 5 repetitions at a difficulty where you can perform 5 clean reps – at least in the early sets – even leaving a few reps “in the tank” and not pushing through the difficulty until the later sets. He even recommends dropping to 3 or 4 reps in the final sets.

I use workouts as a way to regenerate. If I feel depleted after a session, then usually I’ve overdone it. Those of us who don’t compete in strength sports can occasionally overreach, going closer to failure. How often? Less than once per week. Once per month seems more appropriate to me. These sporadic workouts deplete your strength, which means a larger rebound but also a longer recovery.

5. Feel Reps, Don’t Just Count Them

Obsessive rep counting can distract from a certain flow and turn movement into a chore. Instead of counting reps, try to feel them.

With that said, it helps to have a way to track your overall progress. Backfilling is a method of progressive overload to get you past plateaus.

Here’s how it works:

Find an exercise you can perform in the 5-8 rep range with near-perfect form.

In the first set, perform the total number you can do with good form.

Rest for 5-15 minutes.

See how many “clean” reps you can do in the 2nd set.

Rest for 5-15 minutes.

See how many “clean” reps you can do in the third set.

In your next workout, you perform the same number of reps in the first set – it should feel easier, but don’t increase the reps just yet. In the second and third set, you should be getting closer to the number of reps you did in the first set, and ditto for the third. Eventually, you will be able to perform all three sets with the same amount of reps, and at that point, you will be ready to increase the number of reps (or the difficulty) of the first set.

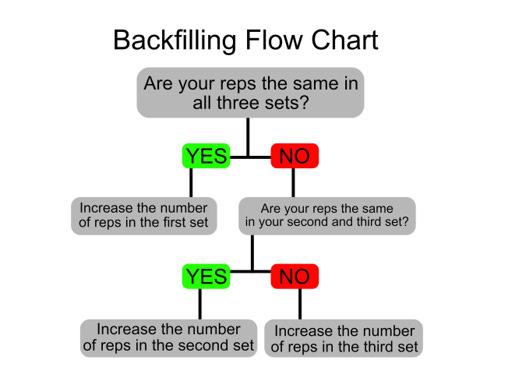

Here’s a helpful flow chart from a book called Grind Style Calisthenics by Matt Schifferle:

For example, a pull-up progression might look like this:

Workout 1 - 3 sets:

8 reps

7 reps

5 reps

Workout 2

8 reps

8 reps

6 reps

Workout 3

8 reps

8 reps

8 reps

You only increase reps of difficulty after reaching parity across all three sets, and don’t increase reps past 10-12 per set.

6. Use Qualitative Progression to keep overall reps low.

If your goal is maximum hypertrophy, i.e., big muscles, you can continue to increase reps with the backfilling method ad nauseam. However, you will get diminishing returns to pure strength, and you may compensate for the increase in volume by overeating. This will not get you the trim waist and harmonious proportions embodied by the Grecian ideal.

Qualitative progression means performing more and more difficult variations. Unlike quantitative progressions of adding weight or reps, qualitative progression ensures that you are subjecting your muscles to unaccustomed stress, maximizing the hormonal response. Too much of the same thing and you will plateau.

The bodyweight exercise Reddit has a helpful resource for progressing to increasingly difficult variations of basic calisthenics exercises. Their protocol involves training the full body 3x per week, doing 3 sets of 5-8 reps of 9 exercises. Personally, I find this type of workout (which is supposed to take around an hour) somewhat boring – especially once you reach the most difficult exercise.

I am working on a database I call the “Katalog,” which includes hundreds of movement/exercise variations and progressions so that you never have to get bored of a particular movement. I plan to release a beta version to a group of newsletter subscribers sometime in the next 2-3 months. If that sounds useful, subscribe and stay tuned.