From Dad Bod to Greek God (Part 2)

Why it's (almost) impossible to build an ancient Greek physique in the modern world.

In Part 1 of this essay, I took up the question of why we see so few living examples of people that embody the classical “Grecian Ideal” of physical beauty. The reason, I claimed, is that nobody trains like the Ancient Greeks did. However, the deficiency goes deeper than mere technique.

In The Abolition of Man, C.S. Lewis blames modern education for breeding “men without chests.” Lewis’s wording here should not be confused for a superficial critique of soft, weak, modern man. By “men without chests” he doesn’t mean those lacking a robust upper body (although there may be a correlation). Rather, he is talking about the chest as the seat of the heart, with its innate capacity for feeling.

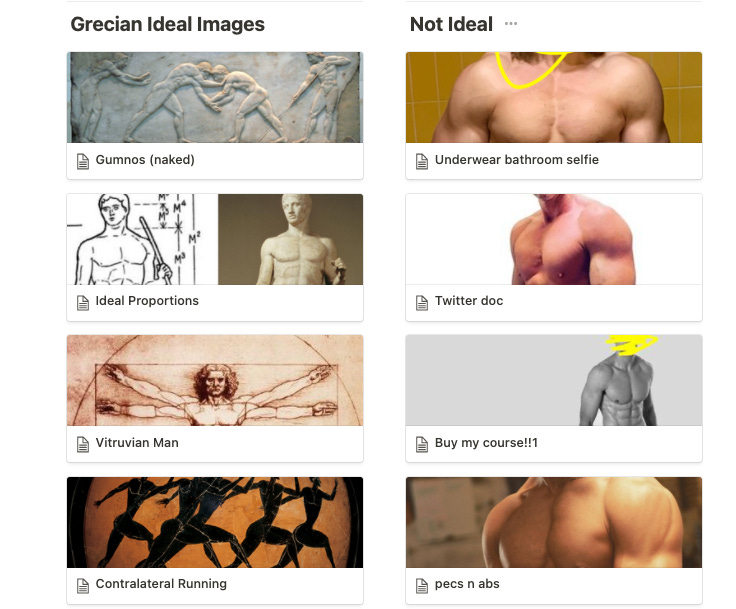

I maintain a collection of images with two columns that illustrates the distinction between ‘men with chests’ and ‘dudes with pecs.’ The left column features ancient and renaissance sculptures, images on Grecian urns, carvings in bas-relief, along with Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man and a few shining exemplars from the Golden Age of Bodybuilding. I refer to this as the Grecian Ideal.

The right column includes a handful of shirtless selfies and vanity posts from online fitness entrepreneurs selling courses like Shredded in 8 Weeks or Less. While many of them are impressive in their own way, these I simply label “Not Ideal.”

You can have big muscles and still lack a chest, in Lewis’s sense of the word, and you don’t need to be ‘yuuuge’ to possess one either. Take the Michelangelo’s David. Scripture tells us that David was the least physically imposing of his brothers. Yet he’s the only one immortalized today as a 17-foot marble statue – bigger than the giant, Goliath, whom he slaid.

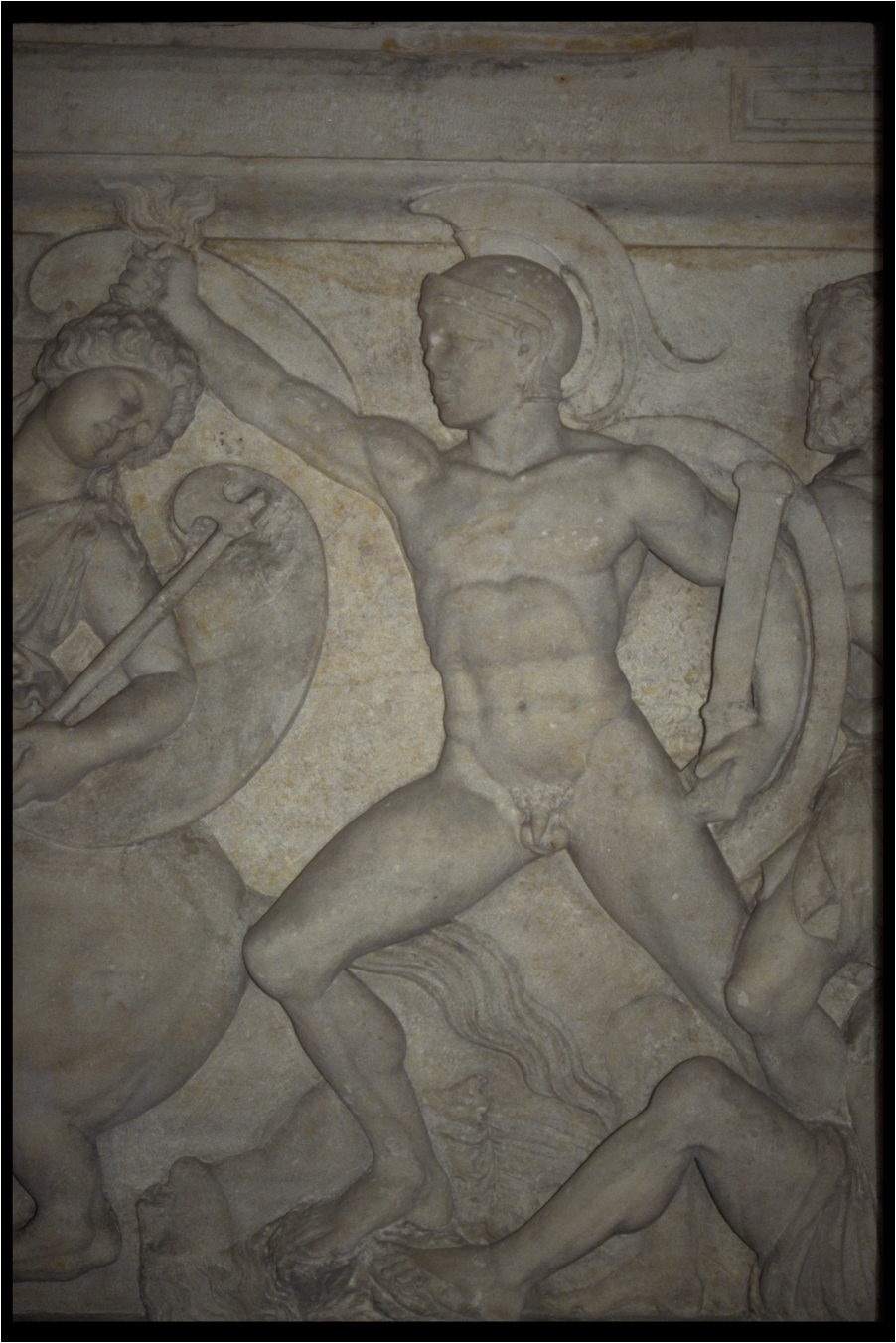

As a young man, David was a shepherd who built his body by trekking through rugged terrain. We can imagine him carrying the proverbial lost sheep back to the herd over his shoulders – his chest pressed out to brace the load and protect his spine. What stands out in the sculpture is not a pair of bulging biceps, or six-pack abs but poise and uprightness. The marble form reveals that Michelangelo’s model had a particularly strong transverse abdominus — i.e., the abs beneath the “six-pack” or rectus abdominus. These muscles act as part of the ‘inner corset’ that braces the upper body against external forces. Although invisible from the outside, the strong tranverse abdominus is implied by the form of the body whether it’s displayed in motion, as in the sculpture below, or at rest, as in Michelangelo’s depiction of Davidic dignity.

If this physique was the norm in ancient art, why is it so hard to find any photographs of modern people that look like this? Where have all the warriors gone?

For one, it’s hard to train transverse abdominus in a traditional gym, since it requires moving weight, not just lifting it. But beyond that, the perfected “Greek physique” can only come from a lifestyle that continuously engages a person in meaningful physical effort. The harmony and proportion of the physical form are byproducts of a vigorous life in service of a purpose.

In contrast, shirtless selfies almost always depict men slouching. By hunching the shoulders forward, you contract the chest and abs and exaggerate their definition. However, you also cement a submissive posture. This trademark shoulder slump signals a polite decline to the summons of a life of adventure. It’s easier to log a few hours in the gym doing crunches and bench presses than to pursue an embodied mission – to find something worth caring about enough that it motivates you to step up to a real-world challenge. If we want to emulate look of an ancient statue, this is the logical place to begin.

According to Lewis, the weakening of man’s spirit began with the advent of modern education. What makes schools distinctly modern is that they teach students to be skeptical of emotion in the guise of “critical thinking.” A side effect of a purely fact-based education, however, is a skepticism of the very idea of objective values. We claim to value courage, creativity and drive, yet strip young men of these positive ideals in favor of a phony intellectualism that denies a natural order in which such things can be called Good.

The proper role of education and the intellect, in Lewis’s view, is to order emotions and guide the passions to a love of things that is proportional to their inherent goodness. The head, he says, must govern the lower animal appetites through the chest. Emotions can be said to be rational insofar as they correspond to an appropriate feeling toward the thing in question.

This will sound familiar if you read Part 1, which presents the classical virtue of kalokagothia – the Beautiful Good. Philostratus, one of the foremost physical educators of antiquity, emphasized the need to align training methods and techniques (techne) with wisdom (Sophia), such that they would bring about the greatest good.

In other words, motives matter. Health and strength are good because they enable people to enact a vision of the good. Once the head determines the best course of action, the body must be also capable of following the directions.

Instead, muscles are often pursued purely for their aesthetics. Thus, those who place little value on “looking good naked” are left to believe that fitness is relatively unimportant. To their credit, many men are using the gym to discipline themselves to escape the traps of modern mediocrity, from porn addiction to substance abuse. Physical challenges like weight lifting and the like do have some inherent value as disciplines. However, the methods of lifting heavy things and isolating muscle groups fail to produce beauty (and often lead to injury) because they neglect harmony of proportions and the integrity of the human person as a purposeful actor.

Physical education must be restored within a curriculum that also teaches young people how to think about what’s worth pursuing – to order their affections toward the good, and then train the body to obey. Without purposeful action in pursuit of the Common Good, civilization will always slouch toward Gomorrah. It’s not just the selfie dudes hunching over in front of their phones. At the behest of our smartphone addictions, we’re all deforming our bodies through a literal slouching posture known as “text neck.” They say this is even leading to the growth of a vertebral spike between the shoulders and cranium.

In short, we are devolving.

This isn’t happening because of some fundamental scarcity in our environment, or a decline in vital brain matter. Instead, it’s happening because we’ve become affixed to lower things. We don’t know what to value or pursue, and so we obsessively look to our phones for guidance (I am speaking here to myself as much as anyone). Our bodies reflect that. Slouching in front of our phones and computers is actually a maladaptation to the self-imposed demand of being plugged in all the time. It’s the position that requires the least energy to maintain while looking at a screen for long periods of time.

Lifting weights for a few hours each week doesn’t fix the fundamental posture we’ve adopted towards technology, or the physical defects this posture breeds.

The statuesque physiques on display in museums of ancient culture were not primarily built in the gym – especially not the cramped and sterile box gyms we have today. The ancient Greeks may have trained their bodies in outdoor gymnasia, but their chests were forged in the course of quests that expanded the frontiers of human knowledge and civilization. They trained for a reason.

The world has enough gurus peddling Get Ripped Quick schemes. We need more perspective or context on why physical strength matters, or how it can be ordered within the broader universe of good things. Without an answer to this question of “why?” fitness is futile at best and vain at worst.

When we look the statue of David, we don’t feel inspired to emulate his workout program, or even his occupation, but rather the values and manly virtues he embodies. There is a link between the shape of the body and the contents of the soul – between the literal chest and the heart and blood that pump within it. Man must have an ordering purpose – a concrete vision of the Good – or else he will lose his chest.