I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again:

A vigorous life is the best training for a 50-mile march, and a 50-mile march is the best training for a vigorous life.

We’re coming out of Northern California’s rainy season, and spring's brief, green, mercy is already surrendering to Bangor’s dry summer heat. With it, my window for lighting burn piles will end. Since November, the bulk of my hard workouts revolved around burn piles – sawing, stacking, and setting logs on fire with the tinder of their dried-up branches.

Without the added purpose of clearing land, it would be hard to find the motivation for this as mere exercise. Some find lifting heavy things to be its own reward, but I find it far more satisfying to throw them into a blazing furnace and watch them crackle.

During Lent, I tried to make up for lukewarm fasting with this laborious chore—a kind of penance by poison oak.

"Ora et labora," urges St. Benedict in his Rule for monastics—prayer and work.

Every man must have his "why".

A good, strong "why" makes meaning out of labora and impels you to exert yourself harder than you otherwise would or could.

It helps to have a "why" when you’re trudging up a hillside with a wheelbarrow and hit a stubborn rock, or singe the tips of your hair getting too close to a blazing fire.

It's essential to have a "why" when my glasses fall off while I'm waist-deep in poison oak.

Especially when I reached the property’s final frontier: the deep dark woods. The tangled thicket of oak and poison oak required me to wear nylon painter's coverall like some backwoods hazmat technician. Only instead of handling toxic waste, I was reclaiming long-abandoned footpaths from several seasons of neglect.

I have a theory that poison oak is possessed by an alien, malevolent intelligence that thrives on neglect. Like rattle snakes, mosquitos, star thistle and other things that bite, it finds its niche because of Man’s fall from grace, and neglect of his original job as gardener. Within my amateur theological scheme, Man is ultimately called to resume this vocation—but with full, conscious, and active participation rather than in Adam’s naive state of wonder. But in exile, Man must work the land "in the sweat of his face.”

My “why” for clearing the deep dark woods is several fold.

First, the effort itself is a well-rounded form of physical training.

Second, I am making a path for the countryside obstacle course I've envisioned since we first arrived here. It’s oddly satisfying to walk unhindered through a landscape that was once impassable, and to imagine what it could be in a couple more burn seasons.

But the third and deepest "why" that keeps me going is a sense of purpose and identity that has become more clear in the past year of living on the land: becoming an Athlete of Life.

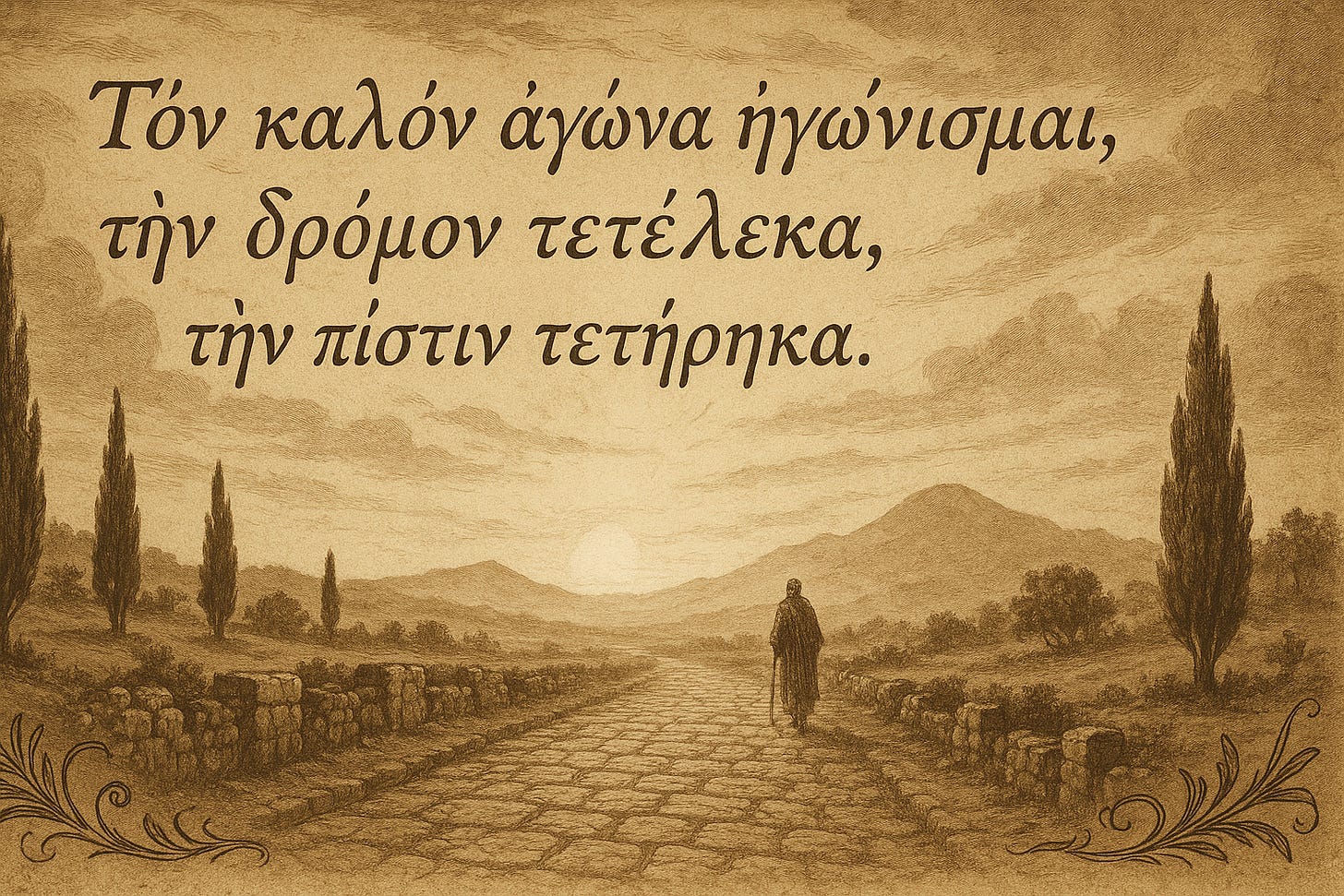

Saint Paul first conceived this category, though we've largely forgotten it. In his letters, he frequently uses athletic metaphors: "I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith." He urges us to "run in such a way as to get the prize" and to discipline our bodies like athletes in training. For Paul, physical training paralleled spiritual discipline—both requiring sustained effort toward a higher purpose. While he acknowledged that "physical training is of some value," he saw it primarily as a tool for something greater.

On the first page of Georges Hébert's training manual for the natural method, he echoes this ancient wisdom: "The primary purpose of physical education is to develop general fitness, the foundation of health, while also building proficiency in all essential practical exercises."

The central concept is développement foncier—foundational development. While Hébert wasn't writing about spiritual life, his philosophy gets closer to the ideal of being strong to be useful rather than in pursuit of some vain discipline or specialized sport.

I consider it a supreme blessing to have fallen under Hébert's influence in my early twenties. Until then, I had specialized in distance running, which had already taken its toll with repetitive stress injuries and a general boredom with "exercise."

In 99% of cases of chronic sedentarism, the inactive person is not lazy. They're bored.

Stacked against the varied demands of our paleolithic ancestors or even the neolithic farmer, modernity asks little diversity of movement. Even the more enlightened corners of the fitness world regard non-sport exercise as something that fits in a separate container. It's a hygiene, like flossing your teeth.

Instead, I've come to think of movement as a practice: a skill to be learned, improved, and mastered. What used to fill the compartment of "exercise" now spreads across what Teddy Roosevelt called the strenuous life, what Ray Peat referred to as a stimulating life, and what Kennedy called a life of vigor.

For all of these men—Hébert, Roosevelt, Kennedy, and Peat—health was good in itself but primarily as an enabler of higher things. For Hébert, this was voiced in his slogan, "be strong to be useful." For Roosevelt and Kennedy, it was bound up in the ideals of vigorous citizenship and American progress.

Life is too short for treadmills and siloed exercises you don't enjoy.

There is so much work to be done. Yet most people—even the active ones—expend their most arduous effort on spinning machines or elevating bricks on pulleys without building anything of lasting value.

We need to elevate a new category in the popular consciousness: the Athlete of Life who cultivates his virile energy in pursuit of a mission. He does not compete for trophies or train for specific sports. He reaches an elite level of functional capacity applied to his own real-world vision.

For me, this remains an aspirational identity. I am still making the path, still training for a mission that only reveals itself in increments, proportional to my capacity to receive it.

The Framework for Renewal

In years past, I've taken an ad hoc approach to my training for the 50-mile march, assuming a vigorous baseline lifestyle would carry me across the finish line.

However, with each passing year, I've encountered more difficulties from uncooperative body parts. The spirit is willing, but the ankles are weak. Winter pounds arrive easier; summer shedding grows harder. I could blame "aging" but I've come to see the real culprits as apathy and cumulative, unintentional stress.

To combat these dual nemeses of the vigorous life, I've been developing a training framework for renewal. There are many trendy discipline programs out there – from Exodus 90 to 75 Hard – that encourage ascetic practice for a set period of time. But not all of the practices are necessarily health-promoting (drinking a gallon of water per day or daily cold showers regardless of thyroid health, for example).

In my framework, askesis (discipline) takes a backseat to zoe (vitality). We are approaching the season of Pentecost, after all – not the penitential period of Lent. Furthermore, life is a marathon, not a sprint (though, ironically, the best training for a marathon ruck turns out to look more like a series of sprints than a string of stressful endurance feats).

My philosophy of foundational development has matured into what I'm tentatively calling the New Stress Synthesis – blending the generally anti-stress bioenergetic perspective of figures like Hans Selye and Ray Peat with the pro-stress “hormesis” perspective found in the mainstream of biohackers (think ice baths, fasting, and carnivore).

The synthesis is this: your must push your limits, without surpassing them. And in doing so, you increase the threshold at which stress sets in. So if and when life necessitates surpassing them, you’ve prepared such that the damage is limited.

The 50-mile march is the case in point. There is no getting around the fact that walking 50 miles in one day is a stressful event. It would be unwise to undertake it without preparation. But with the right training, we can mitigate the harms and transform it from a depleting ordeal into a fortifying trigger for growth and adaptation.

My training approach draws from the ancient Greek Tetrad – a four-day training cycle used by warriors and Olympic athletes. Each day had its purpose: preparation, intense training, active recovery, and moderate training. This natural rhythm allowed for sustained progress without burnout.

The goal is increasing the threshold at which you enter harmful stress by staying there only very briefly – just long enough to trigger adaptation. To expand your "production possibility frontier" (to borrow an economic term) of useful, purposeful output. So you can eventually work all day, sleep all night, and return to the same work the next morning with undiminished vigor.

I'm still prototyping this framework, and in the coming weeks I'll be writing more about the main pillars of the Athlete of Life's training:

Conditioning - Your ability to recover from a given amount of work.

Metabolic Flexibility - Your ability to switch efficiently between different fuel sources.

Grit - Your capacity to endure extreme conditions without triggering the stress response.

We’re expecting our fourth child in early July, so the timing of this year’s march remains uncertain. But the training won't be wasted regardless. Some challenges involve clearing poison oak and building burn piles. Others arrive swaddled in blankets. The Athlete of Life prepares for both.

On penitence and poison oak .... :-) Keep the fires burning... (Motivational fires, that is... to go along with the very controlled California burns, of course... )

Hi Charlie, I really enjoyed this article!!! With my gardening business I am constantly trying to find a balance between hard work and rest, usually finding it via injury. Super annoying. I am excited to read more about how to find limits without passing them. This is exciting!

Congratulations on living such a fun and challenging life, and growing a beautiful family. Jane. 😊