Lighter. Better. Faster. Stronger.

Long-distance walking may be the single best way to get in shape. Here's how to do it without getting hurt.

“The World Reveals Itself to Those Who Walk.”

–Werner Herzog

When people are feeling slugging and overweight, they have a tendency to try to brutalize themselves back into shape after years of inactivity. Sometimes it works. Usually, they get hurt or burn out.

Hitting the treadmill with poor form, they jolt their deadened joints awake from their slumber. The combination of cushioned shoes and hard, monotonous terrain exposes the feet, ankles, knees, and hips to dangerous repetitive stress.

Just as children must walk before they can run, adults coming off of a lengthy sedentary phase need to relearn to walk before adopting more vigorous forms of exercise. Chronic sitting actually causes “gluteal amnesia,” a form of physiological memory loss, in which your butt muscles forget how to fire properly because they’ve become stuck together – laminated by continual compression in the chair.

But before you order a standing desk, consider getting up and moving outside instead. Take that work call on a walk through your neighborhood. Schedule a hike with a friend you haven’t seen in a while. Just doing it is the best way to recover your body’s forgotten knowledge of proper form, but if you want to set a proper foundation, this guide is meant to educate sedentary modern humans on ancestral walking technique.

The Biomechanics of Bipedalism

BIPEDAL BY NATURE

Our ancient ancestors literally walked everywhere, so they were presumably pretty good at it. We should trust our body’s organic intelligence, as Case Bradford says.

Long-distance movement was essential for our nomadic ancestors, who foraged and hunted smaller areas often to the point of scarcity (or even extinction). When they moved on to greener pastures, they walked. Walking upright is actually more costly in terms of energy than walking on all fours – so it must have had other advantages. Some speculate that our hominid ancestors came down from the trees to the swampy deltas and had to hang and swing from branch to branch. This may have eventually led to upright walking.

Whatever happened those many thousands of years ago, there’s no disputing this fact:

We are all walkers now.

Walking evolved as the most efficient mode of locomotion for Homo erectus. Although not as fast as running, it uses less than half as much energy over the same distance.

One consequence of moving from four points of contact to two is that the body’s entire weight now rests on a smaller surface area. We must find balance between the small points of the balls and heels of the feet. The foot is the foundation of bipedal locomotion.

If you screw up the foot, then everything you build on top of it will get all “jacked up,” to use a technical term borrowed from biomechanical guru Katy Bowman.

The foot has 26 bones, 33 joints, 100 muscles, tendons, and ligaments, plus 200,000 nerve endings which enable us to “see” the terrain much like a dolphin applies sonar to navigate in the water.

Marching Technique

We messed up our feet gradually and fixing them takes time too. However, you can practice Efficient Marching Technique throughout the day, bearing these stages of the gait cycle in mind.

1. FOOT POSITION

In his Practical Guide to Physical Education, Georges Hébert goes to great pains to make clear that the feet should be “pointing in the direction of the walk.” As opposed to backwards, or sideways? While this may seem obvious, many people have a tendency to slightly internally or externally rotate their feet. Lining the outsides of the feet in parallel with a box produces the preferred form and ensures that you are propelling yourself 100% forward when you walk, not laterally (a common inefficiency).

2. POSTURE

Before you start walking, your ankles should be hip-width apart, and your pelvis centered over the back of your heels. Shoulders are placed back, relaxed, and your chest open. Lead with your heart!

Now, your whole body leans slightly forward, providing the initial impulse for forward motion.

3. FOOT LANDING

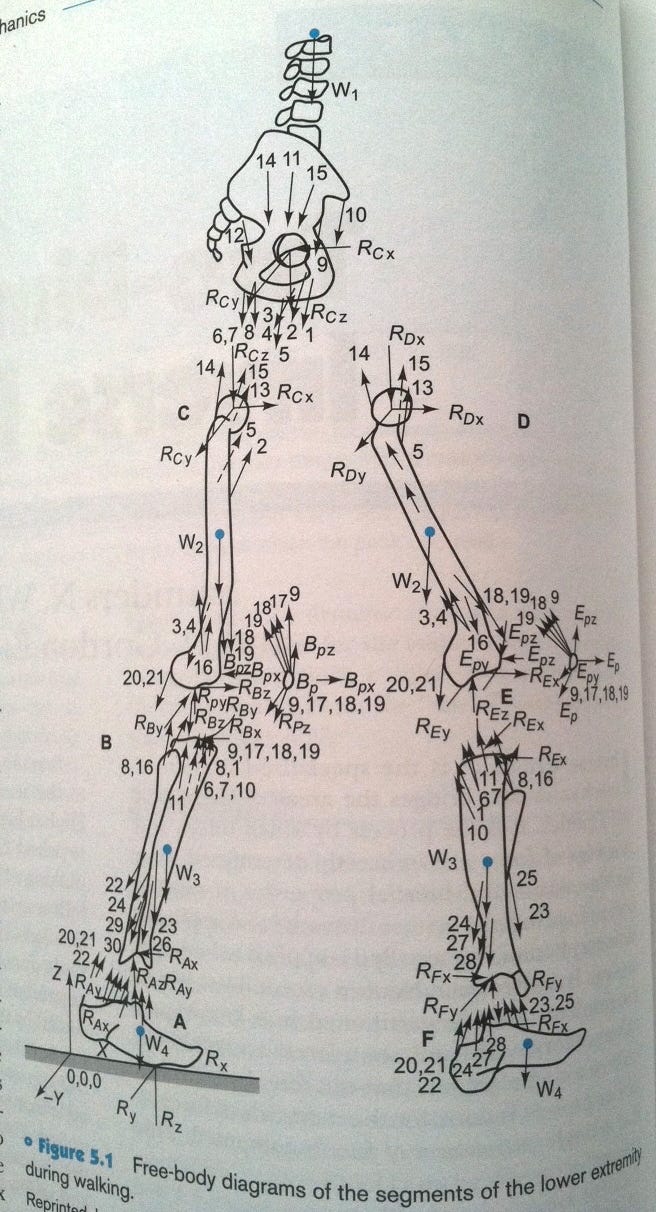

Walking is distinguished from running in that one foot remains in contact with the ground at all times. While this is slower, it’s also much easier on the body. Rather than pounding the pavement, our feet make gentle, shock-absorbing contact with the ground upon landing. The forward leg bends slightly when it comes into contact with the ground, and the heel should land just a split second before the toe rolls forward.

4. IMPULSE

The back leg extends as the front foot lands and rolls from the heel to the toe. Driven primarily by the gluteus medius and gluteus maximus, this leg provides the primary impulse or momentum for forward movement. It is important to fully engage the posterior through the complete range of motion. The knee should not be bent at all when the foot is at the furthest point back. Once it is fully extended, the hip flexors flex to carry the rear leg forward and under the upper body – putting one foot in front of the other.

NOTE: A fully-unbent and extended knee should not “lock” in a hyperextended position. To see what hyperextension feels like, stand straight with your legs extended and try to “lock” them in place – your knee cap will lift up.

5. GLIDE

After extension, the impelling rear leg doesn’t need to lift very high – only enough for the foot to clear the ground. This both conserves energy and prevents excessive downward force upon impact when the foot lands again.

Esther Gokhale, after observing primitive populations around the world, developed a technique known as “glide walking” to describe this in more detail. The pushing-backward motion of the glutes couples with the pulling-forward motion of the quadriceps to produce a smooth and balanced “glide” that works the glutes and gives them a nicer shape over time.

In between these impulses, the hip flexors, psoas, and abdomen (primarily the rectus abdominis) act as a pulley to swing the leg forward:

“The axis of the ankle and the pulley system of the posterior leg muscles require this [foot] position to generate maximal torque without friction.”

— Katy Bowman on Stance

Allow the leg and foot to swing as far forward as they can - like a pendulum - before landing. This both extends your stride and eases the impact. The foot moves forward rapidly on the horizontal plane while barely moving at all on the vertical plane.

For a video demonstration of this section, watch P.E. 101 How to Walk with Gliding Gait by Ron Jones:

“Your true kingdom is just around you, and your leg is your scepter. A muscular, manly leg, one untarnished by sloth or sensuality, is a wonderful thing.”

–Alfred Barron, Foot Notes, Or, Walking as a Fine Art, 1875

Footwear

PARADISE LOST

At some point, probably not long after Adam and Eve ditched their fig leaves for clothing, humans realized that they hadn’t just been naked in the Garden – they were also barefoot. And so they set out to shield the precious architecture of the foot – honed by millions of years of evolution in contact with the earth – with the primitive technology of shoes.

The problem with most modern footwear is that it artificially modifies the shape of the foot – sacrificing sensitivity to feedback for alleged protection. As shoes have “improved,” they have filtered out more and more information from the ground and altered the physiology of the average person’s foot. While it may feel more comfortable short term, the forces absorbed are being redistributed to other parts of the upright chain that result in long-term wear-and-tear.

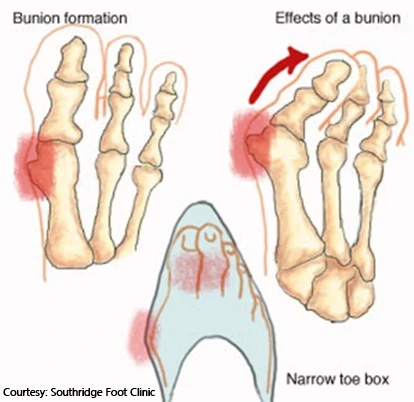

Rather than conform to the shape of the foot, most shoes force the feet to conform to their narrow shape. High heels and narrow pointy-toed boots mimic Chinese foot binding to a lesser degree.

These changes have altered the natural gait and physiology in significant ways. For example, irregularities like pronation, supination, and lack of arches are more often caused or exacerbated by “supportive” footwear than fixed by them. The foot’s natural architecture is arched. When it’s propped up artificially, the architecture weakens. Excessive cushioning nullifies the need for the tough pad of fat beneath the heel, which is designed to cushion the impact on the bones. This simultaneously erodes our natural protection while also allowing a much more forceful impact on hard pavement without an immediate pain sensation. Think of how the new and “improved” football helmets have led to more brain damage – cushioning allows bigger impacts to go unnoticed until serious injuries set in.

⚠️ BEWARE THE PODIATRY-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX TRYING TO SELL YOU MOTION CONTROL SHOES, STABILITY SHOES, OR CUSTOM ORTHOTICS ⚠️

Going barefoot provides maximum feedback from the ground which promotes better walking and running form. Foot position adapts to the terrain when in direct contact, naturally improving your form. Recall that the 200,000 nerves in our feet help us to “see” the ground (like a dolphin sees with sonar). With this feedback, we subconsciously adjust our stride to minimize unnatural torque – the signal that we are damaging our tendons, joints, and ligaments. Furthermore, bones strengthen under compression.

Our feet and legs evolved to handle these positive stressors without injury, although it would be foolish to attempt to go everywhere barefoot immediately given the adaptations we’ve made.

A full discussion of these irregularities is beyond the scope of this guide but you can learn more from Katy Bowman’s book Whole Body Barefoot: Transitioning Well to Minimal Footwear.

Minimal footwear offers a good compromise, but even that requires some conscious transitioning period. The two main features of well-designed “barefoot shoes” are a wide toe box, and zero “drop” between the heel and toe.

Lems, my preferred brand of minimal shoe, explains it like this:

“From heel to toe, feet are meant to be close to the ground and toes splayed, for two key reasons. The first is that this barefoot stance creates a wide base for our feet to support a naturally aligned spine, and therefore proper walking and running form. The second is that only feet in their most naked, close-to-the-earth state can benefit from natural proprioception. That's a scientific term for the critical signals that all those bones, muscles, tendons and attachments in our body (in this case our feet) are designed to send to the brain.”

Georges Hébert, the patron saint of this newsletter, echoes the importance of a wide shoe in his Practical Guide to Physical Education, The Functional Exercises:

“Wear wide shoes, which conform to the shape of the foot and not forcing the foot to conform to the shape of the shoe.”

To this, he adds an additional criteria of a low heel – aka zero drop – to aid with glide walking and upright posture:

“The sole needs to be supple and larger than the foot, the heel low and wide. A heel too high reduces the length of the step and contributes to poor posture. A long sole with low heel helps increase the length of the step and allows a complete roll out of the foot.”

There are many options for minimalist zero-drop shoes. Find one within your price range and never look back.

Finally, for long-distance marches and hikes you can wear two pairs of socks – one pair of thin “liner” socks to reduce friction and blisters, and a thicker pair of wool socks for additional comfort, warmth, and sweat-wicking. I also carry a pack of moleskin to cover any hot spots that could soon turn into blisters. Heed the signs early and you can stop the blister from forming. If you’re too late, Moleskin won’t do much to comfort an existing blister.

Cadence and Rhythm: Pacing the March

“The angle of the body and the bending of the leg upon contact with the cround increases as the pace quickens.”

– Functional Exercises: Georges Hébert's Practical Guide to Physical Education

University of Chicago history professor William H. McNeill is one of America’s most widely read and respected historians. His monumental book Keeping Together in Time hypothesizes that “Dance and Drill” have been an integral part of societal development throughout history – even going as far as to speculate that it is one of the keys to our evolutionary success as a species.

Being able to coordinate movements rhythmically would have given our hunter-gatherer ancestors a distinct advantage during the hunt – not to mention the social cohesion and bonding that results from dancing to a beating drum around the campfire. Rhythmic marching has also offered a distinct advantage on the battlefield – merging individual soldiers into a hive mind that will obey orders and overwhelm opponents through superior organization.

While large-scale drills, marches, and other displays of muscular energy have largely gone out of style due to their misuse (primarily by fascist European movements like the Nazis), the power of shared movement can also be harnessed for great good. “Muscular bonding” is McNeill’s term for the connection developed by people who move together. For long-distance marches, Hébert recognized the value of ‘keeping together in time’ and dedicated a large portion of his chapter on marching to the topic of cadence. Moving in step removes some of the mental burden of keeping one’s own pace – plus, a shared burden is always lighter.

Finally, it has been noted that one can dance rhythmically all night long without depleting their energy or motivation, while the same expenditure of energy without the music or ambiance of the dance hall would tire one out after a few short minutes. Hence the use of marching tunes by soldiers to keep up morale and reach the destination in a predictable, speedy amount of time.

An average marching speed is 3-4 mph. The average tempo of a fast march is around 120 beats per minute. Efficiency is defined by the distance covered in a certain amount of time with a given amount of muscular effort. Up to a certain point, a faster cadence initially translates into a longer stride but eventually you can’t increase the cadence further. Instead, faster speeds are achieved by lengthening the stride (i.e., the distance between two landings).

Personally, I try to minimize breaks during the 50-mile march, which interrupt the cadence and momentum. Fatigue and pain sets in much more rapidly once you stop moving. I also don’t eat much. Instead, I try to adapt my body to burn its own fat for fuel. This transition takes place relatively quickly when it is forced to. Even more so if you are in the habit of eating a high-fat low-carbohydrate diet, or practice intermittent fasting with any regularity. If you’re going to pack anything, make sure it’s light and dense (a la Sardines, dark chocolate, nuts). Same goes for water. Bring a small bottle. Most places you can find water fountains along the way. Any additional weight will slow you down more than you would expect.

Conclusion

Whether you’re working up to a 50-mile march, or just looking for a way to get off your butt, regaining your natural expertise as an advanced bipedal hominid is always an ongoing process. We may never achieve the feats of the humans who crossed the ice bridge to north American or the American pioneers who traversed the Great Plains on their westward journey.

However, we can reclaim our birthright as walkers – increasing the amount of terrain within our reach should we ever be left without the transportation we’ve come to rely on. In the event of a natural disaster, we may find that we need our feet and legs to carry us farther than we ever imagined.

Resources

BOOKS

Every Woman's Guide to Foot Pain Relief: The New Science of Healthy Feet by Katy Bowman

Whole Body Barefoot: Transitioning Well to Minimal Footwear by Katy Bowman

Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (Incerto Book 3) by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

VIDEOS/EXERCISES

P.E. 101 How to Walk with Gliding Gait - Ron Jones

FIX YOUR FEET with Katy Bowman, M.S. - [DVD] Gentle exercises for plantar fasciitis, bunions, hammer toe, neuromas, neuropathy, runner’s feet and shin splints.

Expert Ankles - How to Pelvic List - Nutritious Movement

Advanced Foot Position - 10 Minute video. March in place, feet hip-width apart

12 Easy, Anytime Exercises to Strengthen Your Ankles | Livestrong.com by Jessica Smith

Katy Bowman’s Healthy Foot Course

“I personally would rather do the existentially essential things in life on foot. If you live in England and your girlfriend is in Sicily, and it is clear you want to marry her, then you should walk to Sicily to propose. For these things travel by car or aeroplane is not the right thing.”

–Werner Herzog, Of Walking in Ice, 1978